Half of the average brewery’s revenue comes from on-premises sales, according to the Beverage Marketing Association (BMA). So, naturally, the segment dried up when states ordered nonessential businesses — including restaurants, bars and taprooms — to close.

Indeed Brewing, MinneapolisAnd, while many states allowed these operators to reopen by early 2021 (albeit at reduced capacities) BMA data suggests that the segment could lose nearly $880 million this year from on-premises sales as a result of the pandemic.

Indeed Brewing, MinneapolisAnd, while many states allowed these operators to reopen by early 2021 (albeit at reduced capacities) BMA data suggests that the segment could lose nearly $880 million this year from on-premises sales as a result of the pandemic.

Despite the ongoing challenges, many brewery operators are proving to be surprisingly resilient. Through workarounds, some small capital spending and shifts in operational modes, a good number of breweries have set themselves up for success moving forward.

As might be expected, few craft brewers invested in upgrades, production equipment or expansion in 2020. Many brewers indicated that government Paycheck Protection Program funds were spent on wages to keep as many people employed as possible. When brewers did spend, they often used their money on physical changes to their taprooms to comply with COVID-19 guidelines — partitions and air purifiers, for instance — and on software that would allow them to more easily shift to takeout mode.

As winter approached, one of the more popular purchases made by taprooms were igloos. These small shelters, usually seating up to eight people, allowed many taprooms to maintain outdoor seating areas on even the coldest days. This past winter, igloos could be found as far south as Virginia.

Dockside Brewery in Milford, Conn., took the igloo experience to a new level when it created Dockside Igloo Park. The outdoor space consists of six themed igloos, available for two-and-a-half-hour reservations. Each igloo’s name — “Home Sweet Home,” “In Da Club,” “Dockside Cabin,” “Man Cave,” “New England Vibes” and “Shipwrecked” — is reflected in its decor. For example, Man Cave sports a long leather couch and flat-screen TVs, while In Da Club features funky tables and chairs, and even a disco ball.

In the Tri-City Brewing taproom, customers have several seating options, from bellying up to the bar to relaxing around 4-tops perched atop wooden barrels.

In the Tri-City Brewing taproom, customers have several seating options, from bellying up to the bar to relaxing around 4-tops perched atop wooden barrels.

Other breweries, sensing an increased need for products to be shipped, did invest in expanded production. For example, Widowmaker Brewing Co., in Braintree, Mass., increased the size of its production from three 30-gallon tanks to six in order to produce more beer in cans. When it opened in 2017, Widowmaker didn’t even focus on canning its beers, preferring to serve its rotating slate of brews in its 70-seat taproom. The venue’s L-shaped bar features 10 taps lined up against the back wall, a setup that is becoming a more common layout among craft brewers.

“As we’ve grown, we’ve adapted to the environment,” says Ryan Lavery, co-founder of the four-year-old brewery. “In the beginning, it was about drawing customers to our taproom to try our beers. We figured in time, the desire for cans would come.” Before canning, Widowmaker got its beers out by delivering kegs to selected bars, and growlers to beer and wine stores.

Constant Conversions

The brewing process at Tri-City Brewing. For the most part, craft breweries have done whatever necessary just to stay afloat. Some converted their production tanks to make hand sanitizer. Others shifted to a takeout model.

The brewing process at Tri-City Brewing. For the most part, craft breweries have done whatever necessary just to stay afloat. Some converted their production tanks to make hand sanitizer. Others shifted to a takeout model.

Tri-City Brewing Co. (TCB) is a 14-year-old production brewery and taproom based in Bay City, Mich. President and founder Kevin Peil says the pandemic hit the company hard. Not only did TCB have to shut down its taproom, it also saw its production dwindle drastically.

After the state allowed bars and restaurants to reopen — at 50% capacity — Peil’s team launched into meeting COVID-19 protocols aggressively. “We socially distanced everything,” he says. “We clean like crazy. We do contact tracing. We have touchless menus; people get online to order.”

TCB even upgraded its outdoor beer garden for winter use and installed lights, a wind guard to offset winds coming off the nearby bay and five fire pits so that people could sit outside in all but the most inclement weather.

Tri-City’s taproom is a simple setup, Peil says: a 35-foot elongated bar with 20 taps —along the bar’s back wall, as in the Widowmaker taproom. The full complement of beer glassware, from pints and pilsners to snifters and mugs, is on hand — but no warewashing machines. “We wash all of our glasses by hand,” Peil says.

In addition to the bar, seating consists of high four-tops sitting atop wooden barrels, a series of longer tables and single seats facing the windows. Beyond the bar sits a 60-seat back room where TCB can offer live entertainment. There is no kitchen, so no food menu as such. But customers can bring in their own food, and Peil says food trucks park near the taproom “all the time, and some will actually deliver to your table.”

In Minneapolis, Indeed Brewing Co. pivoted and repivoted so much in the early going that, according to hospitality director Lindsay Slanga, “it felt like whiplash.” Initially, Indeed responded to Minneapolis’s closure orders by setting up a to-go and delivery platform through a service window. Once restrictions began to ease, Indeed expanded seating by sub-leasing the third floor of the building to add square footage for a new “Beerland” space.

“Beerland was created out of a necessity to provide more seating in the safest way possible, moving into the winter months,” Slanga says. “Our hospitality and marketing teams combined forces to create different spaces and experiences for anyone who walked into our space.”

Rustic decor at Stone Corral Brewery—the name comes from an actual stone corral on the owners’ property—now includes a nod to mask-wearing.In addition to the main taproom, Beerland consists of The Lot, The Den and Up Top. The Lot is Indeed’s expanded outdoor space, which has been outfitted with heaters and propane-fueled fire tables. Each night, Indeed converts its loading dock to The Den, with individual spaces that look like sitting rooms and fabric dividers separating each one. Up Top, in the newly leased loft-like third floor, is similarly designed with seating areas demarcated by fabric dividers.

Rustic decor at Stone Corral Brewery—the name comes from an actual stone corral on the owners’ property—now includes a nod to mask-wearing.In addition to the main taproom, Beerland consists of The Lot, The Den and Up Top. The Lot is Indeed’s expanded outdoor space, which has been outfitted with heaters and propane-fueled fire tables. Each night, Indeed converts its loading dock to The Den, with individual spaces that look like sitting rooms and fabric dividers separating each one. Up Top, in the newly leased loft-like third floor, is similarly designed with seating areas demarcated by fabric dividers.

“We also leaned into the to-go and delivery model pretty hard,” adds Slanga, “and transformed our secondary taproom into a corner store called ‘Quincy Corner.’ It’s a one-stop shop for all kinds of things, including snacks, locally made goods, records curated by Disco Death Records, and, of course, beer.”

Sanitation stations and portable air purifiers are strategically placed throughout the indoor spaces and, as in many other taprooms, Indeed has shifted to a reservations-only system to maintain capacity at 50%. Customers can reserve spaces for 90 minutes at a time.

Air purifier at the Stone Corral Brewery

Air purifier at the Stone Corral Brewery

“The response to Beerland was better than expected,” says Slanga. “There are pieces of the current model that have a good chance of sticking around even when restrictions are lifted. We’ll relinquish Up Top in mid-May but add additional outdoor spaces in The Lot and on the sidewalk outside Quincy Corner.”

All of the equipment brought into the space for Quincy Corner is mobile. “We purchased slat wall shelving for various sundries, a cooler for cool storage and a freezer for frozen needs,” says Slanga. “We also had an awning installed to shelter guests at the pickup window.” One more item that was added was a custom neon sign to showcase the Quincy Corner brand.

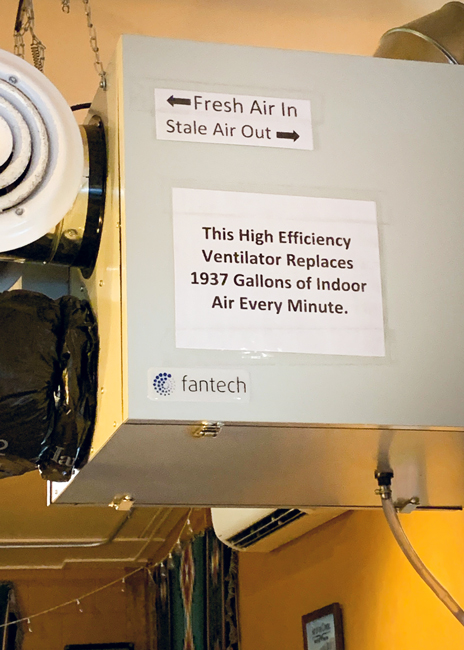

There is nothing portable about the air purifier found at Stone Corral Brewery in Richmond, Vt. Snaking across the ceiling of the brewery’s taproom, the ventilation system removes stale indoor air and replaces it with preheated fresh air from outside. Manager Ben Hamilton says the air scrubber replaces 1,937 gallons of indoor air every minute.

The air purifier represents one of several safety protocols Stone Corral implemented in its 15-tap taproom to abide by Vermont’s COVID-19 rules. The brewery’s quick action is the main reason why Stone Corral has never had to shut down because of a staff member contracting COVID-19, Hamilton adds.

“After COVID hit, we knew we needed to adapt in order to keep customers,” says Hamilton. “So, we repurposed our business model. We shut down the restaurant only as long as we were required to. We went to takeout-only, which came about just as we acquired an online ordering system, which helped immensely.”

The transition to a takeout-only model was pretty straightforward. Instead of plating food and bringing it to tables, Stone Corral culinary staff packaged the food in plastic to-go containers, and runners bagged it up and brought it out to customers waiting outside.

Stone Corral Brewery owners Melissa and Bret Hamilton took pandemic precautions seriously. Not only did they have plexiglas partitions set up between tables to aid in social distancing, they installed an elaborate ventilation system to continually circulate fresh air throughout the taproom.

Stone Corral Brewery owners Melissa and Bret Hamilton took pandemic precautions seriously. Not only did they have plexiglas partitions set up between tables to aid in social distancing, they installed an elaborate ventilation system to continually circulate fresh air throughout the taproom.

Through takeout, Stone Corral sold beer in cans and growlers, food and even to-go cocktails. The cocktails are packed in vacuum-sealed bags to maintain their integrity until customers get them home. Meanwhile, the ventilation ducts were installed, as well as plexiglass dividers between tables, so that when restaurants were allowed to reopen, the Stone Corral taproom was ready.

A more subtle change was made regarding the restaurant’s menu. Customers now can access the menu by using a QR code reader. Hamilton says the shift has been a timesaver as well as a safety measure. “This gives us more flexibility than before,” he explains. “We can change our menu on the fly at very low cost. We can add or remove a menu item, and in 30 seconds the change is in front of customers’ eyes.”