With the complexity of running a restaurant or other foodservice institution, it’s all too easy to lose track of the waste stream. “Controlling waste is about menu, mindset and management,” says foodservice consultant Arlene Spiegel, FCSI, of New York-based Arlene Spiegel & Associates. “At the end of the day, did you sell out or throw out food? Did you overproduce, or are you forecasting production correctly?”

Spiegel advises her clients to use a simple technique to begin to understand food waste: clear plastic buckets, rather than opaque garbage bags, to dispose of all edible byproducts of food prep. Operators can also use waste sheets to track food disposal patterns over time. “Have a paper form on a clipboard somewhere, at the end of the line or prep table or on a desk, noting what had to be thrown out, what was oversold, what came back from a guest complaining it wasn’t cooked properly,” Spiegel suggests. “If food costs go high, it’s typically improper forecasting or overpreparing, or failure to look at expiration dates on the rotation of ingredients.”

The main reason for overproduction in foodservice kitchens is operators’ fear of running out of food, explains Sam Smith, director of marketing for Leanpath, an Oregon-based food waste consulting firm. Tracking what menu items were wasted and why should allow chefs and managers to reduce production of an often-tossed item — with confidence. “Having a tracking station with a smart scale and touch screen enables staff to weigh food waste and identify what it is and why it was wasted,” he says.

If analysis attributes a significant proportion of the waste to spoilage of ingredients, that means “tidying up purchasing and inventory management,” Smith says. If the way staff trim meat or produce contributes to waste, the operator can address it by repurposing some of what’s going in the trash. For example, the operator can use the trimmings to create a croquette or soup stock. Another approach is to educate staff to trim more closely. Taking photos or videos and then acting on the results “can be really helpful in managing trim waste,” Smith says. “By looking at a photo, you might see that staff are leaving too much flesh on the trim and need better training in knife skills.” The most important way to manage the food waste stream is prevention, he adds.

Compost Kings

Will Brown, executive chef at Longwood Gardens near Philadelphia, feels lucky to be able to turn food scraps into a useful product to help grow the botanical garden’s flowers and plants that serve as the main draw for visitors. Longwood has had a composting program for nine years. The restaurant staff has had additional guidance on waste management from Restaurant Associates (RA), which handles on-site dining management on the property, and RA’s corporate parent, Compass Group.

The staff’s first step in turning scraps into compost is collecting them in the kitchen. “Each station has a clear bucket with measurements indicated on the side, and we use that to track how much food waste accumulates in prep,” Brown says. “We look at production levels and how much waste is produced by each menu item prepared at each station. We can see what’s avoidable waste — out-of-date food, overproduction, burnt items. That’s where you can work to reduce food waste. And if we see that 12 out-of-date turkey sandwiches have gone into the bin, we know we didn’t do our job as well as we could have, and that’s something we need to focus on.”

Post-consumer waste, including compostable throwaway packaging, goes into recycling bins. Other than the fryer grease that gets pumped out and replaced with fresh oil on a regular basis, and a couple of grease bins for animal fat to be recycled separately, everything organic finds its way to the compost facility.

Staff dump everything from the recycling buckets into a dumpster behind the restaurant area, with the waste then hauled off weekly to Longwood’s central composting facility. There, staff mix it with other organic material — including plants, brush and/or wood chips — and put it through a grinder. The final step is to lay it out in long rows and flip it periodically to aerate for some six weeks while bacteria turn it into compost.

Combination Solution

Sometimes the solution to food waste requires a variety of technologies. That was the case when Minnesota-based foodservice consulting firm Rippe Associates worked with a tribal casino client that operates its own large composting facility but hadn’t solved the problem of getting food waste from its kitchens to the composting area.

The casino was concerned about manually hauling the buckets to lower-level loading docks, since there had been some injuries related to this task in the past. “You could imagine the inefficiency of going from collecting waste in mobile containers, hauling and tipping it into a dumpster, having the waste hauler pick up the dumpster and take it to somebody to compost it,” says Rippe president Steve Carlson, FCSI. “But there are mechanical ways to grind up waste and send it to the dock that would eliminate all the labor and hauling cost of transport.”

The team “looked at pulpers, dehydrators, vacuum transport systems and digesters,” Carlson says. A utility analysis found a pulper would have used 700 to 1,400 gallons of water a day, whereas a digester system required only 180 gallons. A digester, which liquefies the food into a watery slurry that goes down the drain into the sewage system, also has few moving parts and comes at a lower initial cost than other options. A final purchasing decision is forthcoming.

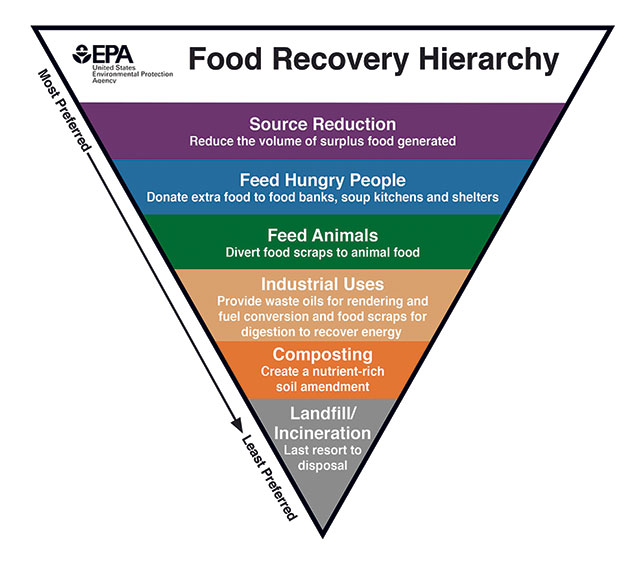

Waste Management Food Recovery Hierarchy Pyramid

Waste Management Food Recovery Hierarchy Pyramid

Today’s Options for Food Waste

In other foodservice operations, the priorities, cost considerations and solutions may be different.

Kerri Fitzgerald, FCSI, principal at Ricca Design Studios, says it’s important to begin by managing purchasing and menu planning. “One piece of equipment, a blast chiller/shock freezer, is key to safely extending the shelf life of food,” she says. “It allows operators to purchase seasonal foods in volume or to make bulk recipes from scratch with far less worry about spoilage.”

Long-term freezer storage can also be important, Fitzgerald notes: “We’re working with a client that practices whole animal butchery; it’s economical for him to purchase multiple animals at once, and more freezer space was critical to his operation.” Nevertheless, there will be food waste at the end of the day, and it must be managed.

Composting might be an ideal solution, but you may not be able to find a partner in the area to process the waste, Fitzgerald says. Operators who want to be environmentally friendly have other options, “such as biodigesters and self-contained anaerobic digestion systems, which also have the potential to create electricity through the process,” she says.

Considerations in choosing one waste system over another can be complex. They include utility costs, hauling costs and operational considerations to determine a best fit. And, for some operators, specific LEED guidelines on reducing utility usage may influence equipment choices.

Fitzgerald gives three examples of Ricca projects where different waste solutions were specified for different reasons. The first example stems from a Mount Holyoke College project, where dehydrators were selected because they significantly reduce the volume of food waste; they blow hot air over food waste while agitating it until it’s a powdery ash that weighs only about a fifth as much as the original garbage. The operator can store the dehydrated material without refrigeration until disposal, as long as it’s kept dry. The college was able to use the dehydrated organic waste as a soil amendment for campus landscaping.

On another project, Hotchkiss School recently decided to add a biodigester for any excess food waste that it can’t send to a farm. The boarding school either composts food waste at its own farm or feeds it to animals at its own or neighboring farms. The biodigester is a closed-box system with a grinder or shredder that breaks up food waste as it’s dumped throughout the day; then, with the addition of water, bacteria or enzymes break it down over several hours, and what’s left goes down the sewer drain.

The University of Pennsylvania considered composting, but that would have meant high hauling costs and would have required refrigerated storage for food waste until pickup in a facility in which space was at a premium. That facility, too, chose a biodigester. “Even with the high utility costs in Philadelphia, it was a more economical solution that required less square footage,” Fitzgerald explains.

Other systems that rely on mechanical processing of food waste but without the final step of biodigestion include scrapper/collectors, which grind the organic waste with recirculating water, send the liquefied part down the drain and separate the tough parts for disposal with other trash. In pulper/extractor systems, in which the grinding and liquefying of waste in the pulper is followed by an extractor step in which the pulp is spun or squeezed to leave a lighter, dryer product for disposal (or for further processing in a dehydrator). Regardless of the solution an operator selects, the conversation around how to handle waste continues to emphasize the growing interest in sustainable practices.