They may lack some of the sizzle and showmanship of other types of foodservice kitchens, but commissary or central kitchens play critical roles in unlocking efficiency, safety, consistency and quality for many large-volume operations.

Found everywhere from hospitals and corporate dining, senior living communities and sporting venues, to caterers, chain restaurants, colleges and casinos, commissary kitchens are strategically designed for heavy lifting. They enable bulk production of meals or meal components and, in turn, enable operators to feed hundreds if not thousands of customers day in and day out.

Once easily defined, the commissary model itself has stretched in recent years to include variations on the theme. Newer ghost kitchens, or cloud kitchens, for example, typically support on-demand cooking for one or more commercial restaurant brands’ off-premises meal preparation needs. With COVID-19 accelerating demand for delivery, this segment is growing quickly. A recent report by Allied Market Research pegged the cloud kitchen market at $43.1 billion in 2019 and forecasts it will grow to $71.4 billion by 2027, led in some cases by third-party pioneers.

Delivery provider DoorDash, for instance, last year unveiled its first DoorDash Kitchen, a commissary/cloud kitchen facility in Redwood City, Calif., shared by three local and two national brand restaurant tenants. Each has a separate, custom-fitted 400- to 600-square-foot station within the kitchen in which the brands’ own employees prepare menu items for pickup or delivery by DoorDash employees. The restaurants utilize designated, secure storage and refrigeration space with common areas.

Other iterations of shared commercial kitchens, often referred to as commissaries, might host multiple small entrepreneurs, such as food truck operators or food artisans selling their products at retail. By virtue of the nature and volume of meals produced there, such kitchens are also likely to resemble those in traditional commercial restaurant kitchens.

A Florida public school district’s cook-chill system enables bulk production of menu items such as taco meat, which is cooked in large kettles, blast-chilled and stored until needed for later distribution to individual schools.

A Florida public school district’s cook-chill system enables bulk production of menu items such as taco meat, which is cooked in large kettles, blast-chilled and stored until needed for later distribution to individual schools.

True commissary kitchens, on the other hand, are a category all their own. Potentially ranging in size from 2,000 square feet to 200,000 square feet, their primary function is to provide a centralized capacity for bulk food preparation that ultimately supports other locations or points of service. “There are different iterations, depending on the operation. Some support a large on-site dining operation, but most also incorporate a transportation function to other points for finishing, rethermalizing and/or service,” notes Paul Mackesey, principal at Madison, Wis.-based consultancy Mackesey and Associates. “We just finished a high school commissary kitchen, for example, that serves that school on the front side but also produces hot food, cold food and bakery items for daily delivery to six other schools in the district.”

That model represents one type of commissary kitchen, in which hot foods are prepared, delivered and held hot for same-day service, eliminating the need to store prepared-foods inventory and to rethermalize on-site. “Many of the commissary kitchens that we design follow a different model, however, which essentially decouples the production process,” Mackesey notes. “Hot foods, such as taco meat, are cooked in bulk in advance, chilled and held in inventory before being distributed and rethermalized for service at another location. Years ago we did a 200,000-square-foot, free-standing commissary and storage facility for a district that supported 140 schools. It centralized full production of core foods, fresh vegetable prep, assembly of hot and cold food items, bakery, with storage for inventorying the items and transportation for delivering them to all schools in the district.”

An inside look at a Discovery Village kitchen in Naples, Fla. Photo courtesy of Fishman & Associates

An inside look at a Discovery Village kitchen in Naples, Fla. Photo courtesy of Fishman & Associates

Benefits, in Bulk

For operators, determining when to invest in a commissary kitchen versus more traditional full kitchens in each location is largely a function of volume and the number of venues within a particular system. Cost savings, especially on labor and kitchen infrastructure, can make central production attractive even for smaller operations.

“It’s definitely a volume issue, but a system doesn’t have to be super-large to reap benefits,” Mackesey notes. “You might have a small K-12 district that has a high school, a middle school and a couple of elementary schools, for example. That’s not a very big program, but the fact that they can centralize some of those laborious processes, whether vegetable prep, casserole production or bakery, is huge. They’re not having to do those same functions in each location, which inevitably leads to inconsistency, but they also don’t have to fully equip and staff each location to handle those production tasks.”

On the commercial side commissary kitchens are increasingly seen as attractive operational solutions as well.

When planning commissary kitchens, transportation is an important consideration with respect to both cost and logistics. Photo courtesy of Mackesey and Associates

When planning commissary kitchens, transportation is an important consideration with respect to both cost and logistics. Photo courtesy of Mackesey and Associates

Bamboo Asia, a four-unit, emerging fast-casual chain based in San Francisco, for example, has made a sous vide-based commissary kitchen a key part of its operating model. Working from a single, 10,000-square-foot facility, staff prep and package all ingredients here for delivery to the individual restaurants. Hot items and sauces are packaged, sealed and cooked in water baths at the commissary kitchen, requiring simple and quick rethermalizing on demand at the unit level — no grills, griddles or hoods needed.

Sufficiently sized and equipped to handle the needs of up to 12 units, it’s a model that Sebastiaan van de Rijt, the brand’s co-founder and CEO, says ensures high quality and consistency of products systemwide. What’s more, the centralized kitchen reduces labor needs and training, shrinks floor space, equipment and infrastructure needs in each unit, and enables Bamboo Asia to develop stores quickly and relatively cheaply. And, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the chain was able to quickly pivot its operating model. As of mid-August, all restaurants remained closed, but Bamboo Asia used its centralized sous vide production capabilities ghost-kitchen style, offering meal components and kits for at-home preparation via advance online ordering with free delivery.

Whether restaurant chain or school district, Mackesey agrees commissary kitchens offer compelling advantages. “We do a lot of rationalization studies for clients,” he says. “The finance people are always interested in the cost-saving piece of it, which can be substantial, particularly with regards to eliminating the need for redundant labor and equipment. But product consistency across multiple locations is another big advantage. With centralized production, you get much closer control of quality, costs and safety.”

Design Focus: Safe, Efficient Flow

On the safety front, commissary kitchens are considered manufacturing or mixed-use facilities and are regulated under a state or local code based on the FDA’s Food Code. Any such facilities that perform special processes, such as vacuum packaging, cook-chill and sous vide, must operate under an approved HACCP plan. And that means designing for proper product flow and handling at every step, receiving through transport.

“If flow is not well planned, it’s not only inefficient but also potentially unsafe for employees, who end up having to cross paths, and the risk of temperature abuse and cross-contamination are significantly greater,” Mackesey notes. “There needs to be a very linear flow. Refrigerated products need to remain in a refrigerated state from receiving and staging through pre-prep, prep, production, storage and transportation. The safest designs are those that segregate cold- and hot-food production areas and enable temperature maintenance at every stage with no cross-over. The ability that technology now affords to manage, monitor and document temperatures makes for a much safer and more dependable process.”

As in any kitchen, Mackesey adds, production and storage areas for raw protein products must also be kept separate to avoid cross-contamination.

Planning and managing product flow in large, free-standing commissary kitchens for optimum functionality and safety according to HACCP principles is relatively straightforward. But, for operations from which an on-site central kitchen serves immediate on-site dining as well as providing food to nearby satellite venues, extra forethought becomes necessary.

Modern senior living facilities represent one such example. As that segment has evolved to offer a more diverse array of restaurant-style foodservice options, central kitchen design becomes more complex. Operators need to answer many more questions before design begins, according to Marisa Mangani, vice president of design at Fishman & Associates in Venice, Fla.

“Our first questions are always, ‘How many mouths — not units or rooms — and what else are you doing?’” Mangani says. “Because in senior living these days, it’s no longer just one big dining room off the kitchen serving a predictable, set menu to everyone. They’re doing a lot of other things. You need to know the full campus configuration, how many exhibition or finishing kitchens they plan, where the various points of service will be, whether there are separate memory care neighborhoods with their own finishing kitchens, what paths food will need to take from the central kitchen to other locations throughout the community. We need to think of their foodservices holistically and then start drilling down on what their needs will be in terms of commissary kitchen design and equipment.”

Mangani cites an example of a recent project, Discovery Village in West Palm Beach, Fla. Plans call for the 325,000-square-foot, 259-unit resort-style senior living facility to be complete in 2024. The facility will include 2 exposition kitchen operations, a bistro with on-site cooking, an assisted-living unit bistro for service only, a memory care unit pantry from which small on-site dining rooms will be served, and a 100-seat main dining room serving 3 meals a day off the main commissary kitchen.

Designing a central kitchen facility suited to serving such a diverse operation requires first drilling down to understand exactly how the operator intends for each satellite location to run, according to Mangani. That requires another series of predesign questions to ascertain each location’s concept and menu, how many employees will staff each area, what level of cooking or finishing will occur at each and what the service style will be.

“Our challenge on the design side is to make sure that the central kitchen can handle all the different kinds of foods going to all of the various locations throughout the day without it being a burden on operations and service,” she says. “When the main dining room is open, that kitchen needs to function as a commercial-style kitchen, but at the same time it needs to function as a production kitchen for all of the other sites.”

To that end, the design Fishman’s team put forth for the new Discovery Village kitchen includes wide aisles, ample storage and mobile prep tables, enabling staff to stage food for distribution to other areas without interfering with activity on the line or service to the dining room.

As operations and menus have become more diverse in many segments, and as consumer expectations for quality and freshness have risen, central kitchens must be designed to do more, adds Bob Daly, president of Fishman & Associates in Venice, Fla. “Food can’t just sit in a steam well. It has to be transported, stored and finished properly at every point of service,” he notes.

As in the case of resort-style senior living facilities, designing for flow becomes more complex. “There now needs to be more doors, for instance, because food is going out to so many different places,” Mangani adds. “Typical flow goes from receiving to storage to prep, production, distribution and back to dishwashing. But now, you have subsets of that having to occur and you don’t want to create crossover. You need to look at the blank space and visualize where all of these food products are going out as well as what’s happening with dishwashing. Will dishes be washed and stored at the satellite locations or brought back to the commissary kitchen for washing? If so, what do those pathways look like, and are drop-off areas and dishwashing in the kitchen sized to handle both the dining room and the satellite areas? If the satellite areas will be serving on disposables, storage space for those products is an issue, as is trash. How will trash be transported through the facility without being an eyesore for residents and guests? And you need to think about distances being traveled, what types of carts are best and where they’ll be stored.”

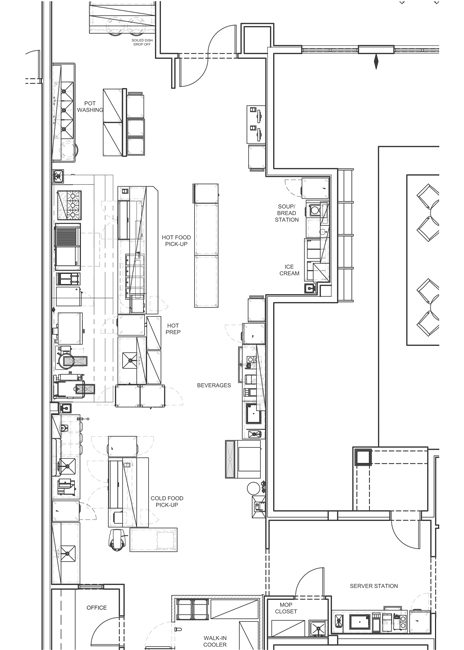

The central commissary kitchen at a new Discovery Village coming to West Palm Beach, Fla., is designed to serve an adjacent 100-seat main dining room as well as several satellite foodservice operations throughout the senior living facility’s campus. Image courtesy of Fishman & Associates

The central commissary kitchen at a new Discovery Village coming to West Palm Beach, Fla., is designed to serve an adjacent 100-seat main dining room as well as several satellite foodservice operations throughout the senior living facility’s campus. Image courtesy of Fishman & Associates

Labor, Yield Drive Equipment Selection

As for commissary kitchen equipment selection, flexibility, durability and production capacity are top considerations, but all must be examined through the lens of menu, labor and anticipated volume needs. Mangani notes standard hot-prep and cold-prep equipment, along with equipment for bakery production, continue to be basic production-kitchen workhorses. Many facilities will include some combination of basic ranges, roll-in combi ovens and convection steamers, braising pans, skillets and kettles, proofing cabinets, mixers and slicers. Larger-volume operations are also likely to include cook-chill systems that enable production and storage of bulk prepared foods.

All can enable operators to produce large quantities efficiently and cost effectively. But specifying the correct size of equipment for individual commissaries is crucial in order to realize those benefits. Key goals in this regard for bulk production, according to Mackesey, are to minimize labor and the number of batches that must be produced.

“Kettles, for example, can range from 30 gallons up to 200 or 300 gallons in size,” Mackesey says. “If you have taco meat on the menu and know that you’ll need 3,000 gallons to meet your system’s needs, you’ll want to consider that 300-gallon size, which can meet that menu need in 10 batches, versus opting for a 100-gallon kettle and having to prepare 30 batches,” he adds. “As you’re doing your production planning, it really comes down to looking at what you need for yields. Efficiency in a central production kitchen is all about trying to minimize the number of batches, which saves both time and labor. Selecting the right equipment, and the right-sized equipment, is what enables you to maximize efficiency and ROI.”