Operators must remain ready to respond if they receive an influx of COVID-19-infected patients in the future.

On the frontlines confronting a contagious virus, acute-care hospitals are beginning to recover from the initial trauma they experienced beginning this past spring. Finding innovative ways to navigate in the new environment, they continue to develop new paradigms for everything from operations to staffing.

Financially, the pandemic delivered devastating results with revenue declines and high per-patient expenses. When patients who want nonurgent and elective surgeries feel comfortable returning to the hospitals, the financial situation will presumably improve but will not likely erase the damage incurred in spring and early summer.

As healthcare foodservice directors and their teams navigate through the COVID-19 pandemic, each day presents new challenges and launches them into uncharted territory.

In the Beginning and After

“Since late February, we’ve been operating at an incredibly fast pace,” says Julie Meddles, MS, RDN, LD, director of Nutrition Services at The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center (OSUWMC) in Columbus, Ohio. “In one of our meetings, the medical director said it well: ‘In eight weeks, we’ve made eight months of decisions.’ He was so right. Since then and during these past few months, we accomplished a lot, experienced a lot of stress and received a lot of appreciation for what we were able to do.”

Jenny Geruntino (left) and Julie Meddles remind patients and customers about services provided.

Jenny Geruntino (left) and Julie Meddles remind patients and customers about services provided.

Faced with myriad changes and tasks, Meddles developed a massive spreadsheet to track all that was taking place, including many new responsibilities. For instance, Meddles participated on a planning team to convert The Greater Columbus Convention Center into a hospital in case it was needed to house and provide food for an increased volume of COVID-19 infected patients. “No one on our staff had ever been involved in planning a convention center hospital,” she says. “Fortunately, we didn’t have to open it. This whole experience is the most surreal thing I’ve ever seen.”

The reality of how serious and devastating the crisis had become unfolded slowly in some communities and like wildfire in others. “Some days were really hard, like March 29, a Monday,” Meddles says.

“That was the day a friend passed away from COVID-19. We both have similar-aged children. My heart was heavy and that day is etched in my memory. It all became very real knowing someone who died from the disease. And we were only 20 days into it at that moment.”

Bill Marks, director, Food, Nutrition and Environmental Services at Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, agrees that the past few months have been the most challenging and difficult in his 30-plus-year hospitality industry career. “We’ve all done things that were stressful, but nothing like this,” he says. “One thing I chuckle about now is recalling that the only thing you could count on was knowing that the changes you made today would change tomorrow as the hospital’s infection department and command center kept receiving new information.”

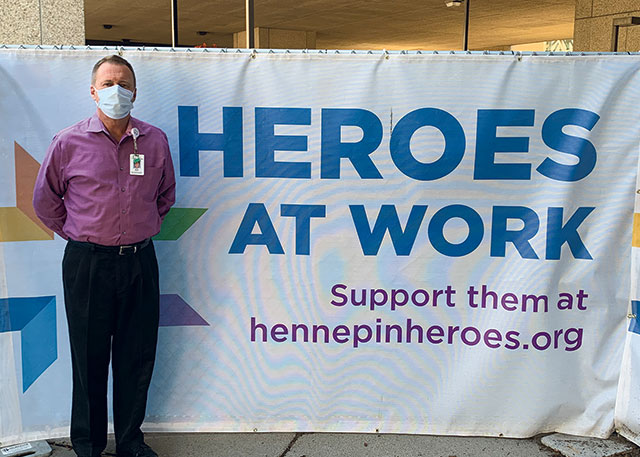

Bill Marks takes a moment to recognize the essential healthcare workers all over the country and at Hennepin Healthcare.

Bill Marks takes a moment to recognize the essential healthcare workers all over the country and at Hennepin Healthcare.

On Sunday, March 15, Marks asked several management team members to meet him at the hospital. “We started talking about all the different scenarios we might face, like what if we have patients in every bed, what if our staff gets sick and how do we get in all core ingredients we need to stock.”

During the meeting, Marks and his team received a message that all the retail stores in the area surrounding the hospital would shut down the next day. “We all looked at each other with ‘holy smokes!’ expressions,” he says. “We had been watching China and Italy and now the virus was here. It felt so surreal. The planning we had to do was incredible. We’ve trained for emergencies and crises, including everything from tornadoes to mass shootings. But we never trained for pandemics. Fortunately, all the training that we had done calls for command structure and we were able to shift quickly into high gear.”

In the first seven weeks, Marks worked every day so he could support his teams in foodservice and environmental services. “This was a difficult time, but in retrospect, I’m glad I went through it because it was so mentally and emotionally challenging.”

During the early days, Hennepin Healthcare had to double intensive care unit (ICU) capacity. “We were fortunate and had built new operating rooms in a new building and so could convert the old ones into ICUs,” Marks says.

At OSUWMC, Hennepin Healthcare and other hospitals nationwide, as COVID-19 cases grew, cafeteria and other retail sales nearly disappeared due to a dramatic drop in people on hospital campuses. This was the result of cancelling elective and nonessential surgeries, hospital employees working from home and patients no longer allowed to have visitors. As time went on, some hospitals reported retail foodservice volume declines of 17% and others reported up to 75%. Foodservice labor was adjusted, with some staff assigned to other hospital positions or furloughed. Generous and morale-boosting food and beverage donations from local restaurants and companies poured in, and at least somewhat cannibalized retail sales as a result.

Finally, in late May and early June when the growth of COVID-19 cases slowed in some areas, hospitals began performing elective and nonessential surgeries again, some employees working from home started returning to work on-site and patients could have one or two visitors. In early July, though, many states reported an increase in COVID-19 cases, which put some hospitals in the hot seat once again.

The experiences of hospitals and their foodservice directors and teams vary based on many factors, including regions of the country, hospital size and numbers of COVID-19 cases. Yet they adopted similar practices in providing food to patients and staff.

For more on Healthcare Foodservice during the COVID-19 pandemic, checkout August 2020's Healthcare Special Report.