Cafeteria and retail sales fell dramatically at most hospitals starting in mid-March. In mid-June when some hospitals resumed elective surgeries and more medical and administrative staff returned to working on-site, various facilities started to report an uptick in sales.

Only a few hospitals have opened their retail foodservice operations to hospital visitors. By mid-July, retail venue participation hadn’t met pre-COVID-19 levels but continued to grow, per various hospitals.

For example, at Hunterdon Healthcare in Flemington, N.J., retail business declined steadily during March and early April to nearly 60% of usual sales and customer volume due to employee furloughs and food donations. Surgeries and procedures resumed the second week of July. Retail business is now up to 95% of sales and up to 90% of volume with food donations declining and employees returning.

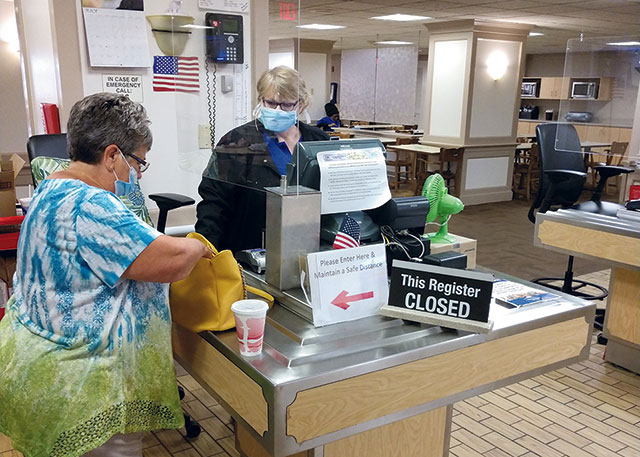

Foodservice teams at hospitals display signage to remind customers to practice good hand washing hygiene and place sanitizing stations in multiple locations in cafeterias and dining rooms. Social distance markers have quickly become standard, with floor makers set six feet apart. At Ohio State Wexner Medical Center (OSUWMC) in Columbus, Ohio, a staff member serves as a monitor to remind customers to maintain social distance. Also commonplace: clear plastic shields to separate staff from customers at counters and cashier stations.

Foodservice staff at many hospitals provide wrapped or individually dispensed plasticware and other disposable items such as boxes and containers holding food and beverages to reduce the risk of contamination. At Legacy WellSpan’s York Hospital and other hospitals, staff increased the frequency of sanitizing all public areas and touch points throughout cafeterias and dining rooms.

Prepackaged salads replaced the salad bar at Hunterdon Medical Center for the time being.To date, all operators interviewed for this article have shut down self-service areas, such as salad bars and deli bars, hot food stations, pizza stations and soup stations. They offer more prepackaged grab-and-go menu items than ever before, including entree salads, sandwiches and pizzas in individual boxes.

Prepackaged salads replaced the salad bar at Hunterdon Medical Center for the time being.To date, all operators interviewed for this article have shut down self-service areas, such as salad bars and deli bars, hot food stations, pizza stations and soup stations. They offer more prepackaged grab-and-go menu items than ever before, including entree salads, sandwiches and pizzas in individual boxes.

Many hospitals now serve soup and other hot foods from behind the serving line at grills and other previously cook-to-order stations. “We had to end our popular bowls made to order because we can’t maintain social distancing,” Hunterdon’s O’Neill says. “We did start our outdoor barbecue menu once weekly at the end of May and are still trying to determine how we can provide the most popular bowls.”

Wellspan converted salad bars into areas for displaying menu items such as prepared salads. At OSUWMC, former salad bars now contain premade salads, wrapped sandwiches, grocery store items like fresh produce, as well as wrapped bagels, cookies, pastries, muffins, breads and fruit. Sanford also converted salad bars to hold grab-and- go menu items.

At Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, Marks and his culinary team wanted to do something special for customers as a replacement for shutting down the salad bar. “We design four gorgeous premade salads and premade sandwiches for each day,” Marks says. “We are very proud of our food quality and don’t want to compromise that. The salads and sandwiches are really spectacular and rotate.”

On June 8, Hennepin opened its cafe grill, but it has not brought back cook-to-order service at any station. At another station, steam table pans display entrees. “To provide faster throughput, we tweaked menus by reducing hot entrees from four to two and stopped offering carved proteins,” Marks says. “We’ve had to start slow to be sure we don’t compromise the food quality.”

Hunterdon Medical Center started its outdoor barbecue menu at the end of May, as usual.

Hunterdon Medical Center started its outdoor barbecue menu at the end of May, as usual.

At OSUWMC, 11 of the 12 retail operations remained open throughout the pandemic. Hours mostly remained the same as pre-COVID-19. Retail volume dropped 55% in March and April overall.

Starting in July, OSUWMC customers could order menu items from a mobile app and pick them up at a central location. They can also come to the cafe and order food from kiosks or place orders with a staff member. Customers pick up grab-and-go menu items, most of which staff prepare in the production kitchen, at display refrigerators or a center island that was a salad bar pre-pandemic. When customers reach the cashiers, they see clear plastic shields separating them from the cashiers. Signage discourages the use of cash.

“We have ordered external card readers so customers can swipe their own credit or debit cards or payroll deduct cards,” Meddles says. “This will cut down on the sanitizing cashiers have had to do in between each transaction. We are focused on mobile ordering to help limit the number of customers in our BistrOH! cafes.”

At Sanford Medical Center in Fargo, N.D., retail volume has taken a huge decline since mid-March and hit an all-time low in early May. Gibson and her team reduced retail restaurant operational hours and closed some restaurants altogether. “Having fast-causal-style restaurants has proven to be advantageous because they are so easy to open and close based on volume,” she says. “The new normal will be much more efficient in terms of operational hours because we have the ability to reset these hours, targeting higher volume times, and reducing hours where sales are low.

At Hendricks Regional Health in Danville, Ind. in March, cafe counts dropped drastically when visitors were prohibited from entering the retail space and when seating was eliminated. Retail cafe hours stayed the same, but only takeout service was offered. By June 75% of the seating was put back in place, Rardin says, and she was able to reopen several action stations offering burgers, salads, quesadillas and omelets. Menu items are offered on china and in packaged takeout containers. “We are still not up to baseline,” she says.

Plastic shields at WellSpan York Hospital help protect staff and customers.

Plastic shields at WellSpan York Hospital help protect staff and customers.

Bare Bones Beverage Service

Beverage service has gone to bare-bones simplicity. At Legacy WellSpan’s York Hospital, for example, staff who stand behind a counter fill only one size coffee cup and hand it to customers. They also hand out packaged sugar and other condiments. Because bottled beverages aren’t offered, staff dispense fountain beverages into disposable cups with straws and hand them to customers. At other WellSpan hospitals, customers help themselves to coffee and other beverages from dispensers. “We’re constantly sanitizing the spigots and service areas,” Bentzel says.

At Ohio State Wexner Medical Center (OSUWMC) in Columbus, Ohio, staff prepare coffee for customers at a center island that was formerly a salad bar. Customers can also select bottled beverages from refrigerated display units.

Dining Spaces

Social distancing in the seating areas in Hennepin Healthcare's cafes, located in Minneapolis, didn’t present a problem in the spring because it was closed for two months. In early June, only 40 people at a time were allowed into the seating space designed to hold 300 people: Chairs were conservatively placed about 12 feet apart.

At OSUWMC, the dining rooms never shut down as state rules exempted hospitals from closing. Staff monitor the seating spaces to ensure customers are properly social distancing at six feet. The number of chairs was cut in half and signage lists the maximum number of people allowed per table. Clear plastic shields surround booths and other spaces to create as many tables as possible. There is no limit for the number of people who can be in the cafe at any one time.

Hunterdon Healthcare in Flemington, N.J., on the other hand, placed clear plastic shields on all tables and each person basically sits in their own cubicle. Barriers also sit near cash register stations, as well.

As Time Goes On

Most operators agree with Hunterdon’s O’Neill, who says if anything keeps her up at night it is thinking about making sure patients and employees stay safe. Clearly patient and employee safety have and always will take priority in a hospital environment. Add to that financial considerations and the hospital scenario looks strikingly different than pre-COVID-19.

Though he wishes for more optimism, Marks anticipates “hospitals will continue to deal with the pandemic and financial constraints for at least a year.” All operators anticipate cafe sales to be lower than pre-COVID-19 as long as some employees work from home and patients’ visitor allotments remain to one or two.

“I worry if we will ever get our customer base back,” Rardin says. “They’ve had months of either bringing their own lunch, working from home or coming to the cafe for takeout. I want to see our dining space filled back up with people chatting and enjoying their meals. I miss that. Ultimately, if the customers don’t come back, we will have to make labor cuts. I don’t want to do this, but we have plans in place and know where we will trim if required.”

Healthcare foodservice operators characteristically look for silver linings whenever crises appear.

Bentzel continually finds time to compliment team members. He speaks for all directors interviewed when he says, “I’m incredibly proud and privileged to work with such a dedicated team from across the system, who, despite their fears and anxiety, have risen above all the challenges and obstacles to selflessly care for all the patients and staff, not to mention doing so in the midst of a pandemic.”

“We will overcome this with time and knowledge,” Rardin says. “There is just so much we do not know about COVID-19, but hopefully over the next two to three years we will learn how to deal and protect each other. People need people and food is often the vehicle that gets us together.

For more on Healthcare Foodservice during the COVID-19 pandemic, checkout August 2020's Healthcare Special Report.