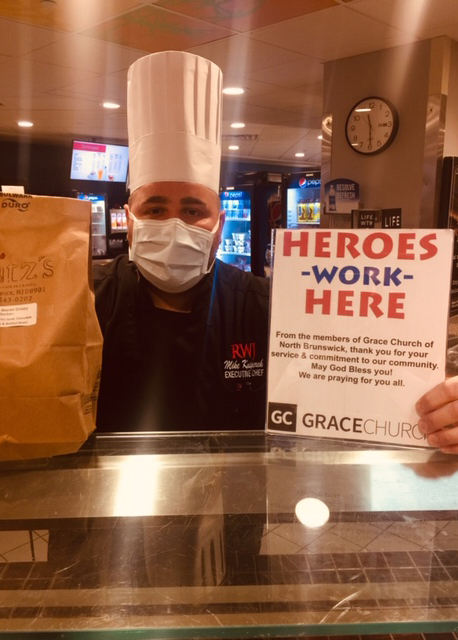

A frontline look as one hospital foodservice team adapts to service during a pandemic.

Serving critically ill patients, as well as the medical teams treating them, is nothing new for healthcare foodservice operators like Tony Almeida. What is new for Almeida, director of food and nutrition at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Jersey, and his peers across the country, is dealing with a fast-spreading pandemic. Here, Almedia shares how the facility’s foodservice team is dealing with its fast-shifting realities.

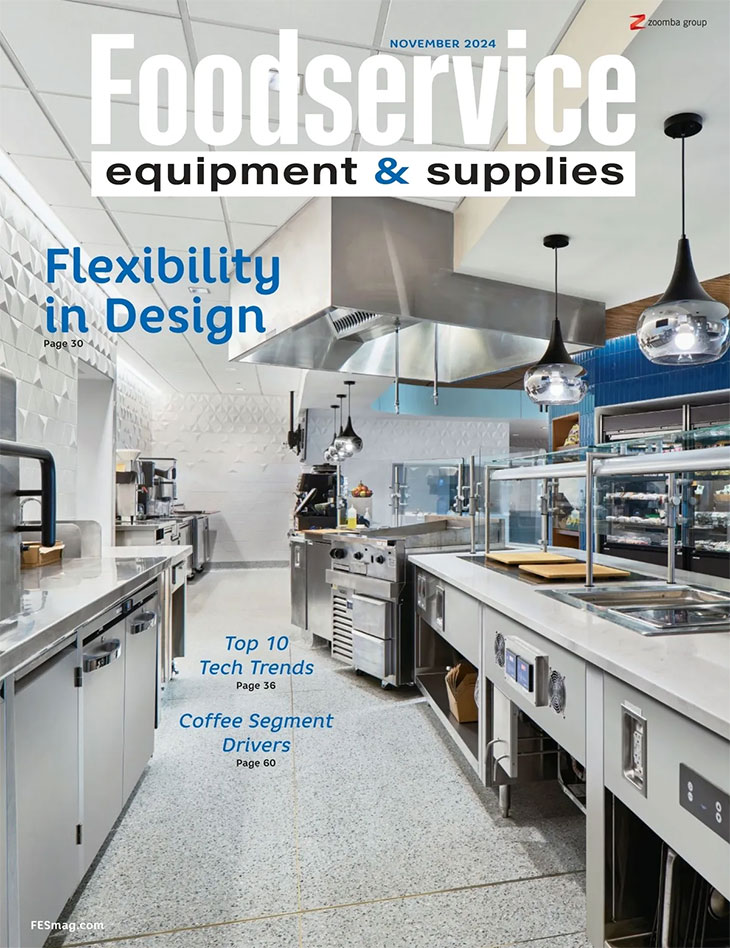

Almeida greets hospital employees as they enter the servery.On April 20, Almeida stood in the hospital’s lobby. It had been six weeks since New Jersey’s governor declared a state of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic and nearly a week since he announced the state’s stay-at-home order. The number of daily cases reported in New Jersey was growing exponentially. Almeida was waiting for a food donation of 250 sandwiches from a local Jersey Mike’s Subs’ franchisee.

Almeida greets hospital employees as they enter the servery.On April 20, Almeida stood in the hospital’s lobby. It had been six weeks since New Jersey’s governor declared a state of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic and nearly a week since he announced the state’s stay-at-home order. The number of daily cases reported in New Jersey was growing exponentially. Almeida was waiting for a food donation of 250 sandwiches from a local Jersey Mike’s Subs’ franchisee.

The donation that day was one of many Almeida receives nearly every day from local restaurants that want to say thank you to healthcare staff working during the pandemic. “In just three weeks, we received $60,000 in food donations,” Almeida says. Donations from 64 restaurants, charities, foundations and other groups include pizza, subs, paninis, sandwiches, fully prepared meals from high-end Italian restaurants, beautifully packaged meals a mayor from a neighboring town donated from a Chinese restaurant and a pallet of Girl Scout cookies from Subway.

Almeida’s system of distribution includes establishing a master list of nursing and other units and offering the donated food to a particular unit as it becomes available. The units’ staff designate a person to come to the first-floor cafeteria to pick up the food. Almeida accepts donations during his regular weekday work schedule and he also comes into the hospital on weekends to ensure distribution of the food.

“We don’t run a for-profit operation,” Almeida says. “The dining room is losing revenue and it’s very nice to see the public is willing to donate. The staff appreciates what these restaurants are doing for them.”

Almeida’s food and nutrition department also offers milk, eggs, individually wrapped cold cuts, cheeses and bread for staff to buy in the cafeteria. Soon after these sales began, a physician told Almeida he should sell toilet paper, too. “We called our distributor, who brought in extra toilet paper and paper towels the next day,” he says. “We’ll sell these items until this is over. People are very appreciative.”

Some time passed before everyone in the hospital knew about the toilet paper and paper towels. “The president of the medical staff, an oncologist, releases an eight-minute video biweekly about what the medical staff is doing for patients during this crisis. He said, ‘You all know Tony Almeida. He does a great job, but I have a beef with him. He should sell toilet paper in the dining room.’ I told him we do sell toilet paper. When I walked by his office, I threw him a roll. On the next video he put in a segment about how we care about the staff.”

Almeida has seen a lot of trauma and crisis management during his 30 years as the food and nutrition director at the hospital. The 610-bed hospital in New Brunswick, N.J., serves as a flagship hospital of RWJ Barnabas Health. The hospital is affiliated with Rutgers Health and features a Level 1 trauma center, one of four in New Jersey. The Food and Nutrition Department always keeps supplies such as water and read-to-eat meals in storage for emergencies and crises.

But Almeida and the staff had never experienced an event of the magnitude of the new coronavirus. “When we first heard about this virus in February, we started stocking up with supplies,” Almeida says. “We had no idea how quickly it would worsen and how many people would be affected.

Employees can purchase prepackaged deli meats, cheeses, sandwiches, milk and eggs along with the day’s menu items such as yogurt parfaits.

Employees can purchase prepackaged deli meats, cheeses, sandwiches, milk and eggs along with the day’s menu items such as yogurt parfaits.

Patient Service

Almeida’s patient foodservice operation continues to offer room service. “Administration has been so supportive and asked us to keep doing the right service for patients,” Almeida says. “We haven’t been asked to downsize the menu.”

When Almeida and his staff realized the crisis was starting and wasn’t easing up, they ordered more water than they normally have on hand for emergencies and hundreds of Styrofoam trays. But these trays were difficult to procure, so the team ordered more paper takeout containers, which they use in the cafe. They ordered 20,000 containers and keep a supply of 5,000 on hand at all times now.

Since the crisis, Almeida’s team leaves disposable trays for patients requiring isolation at nurses’ stations. Once patients finish eating, nurses dispose the trays. The takeout boxes also include beverages in disposable cups.

Patients not in isolation still receive china service.

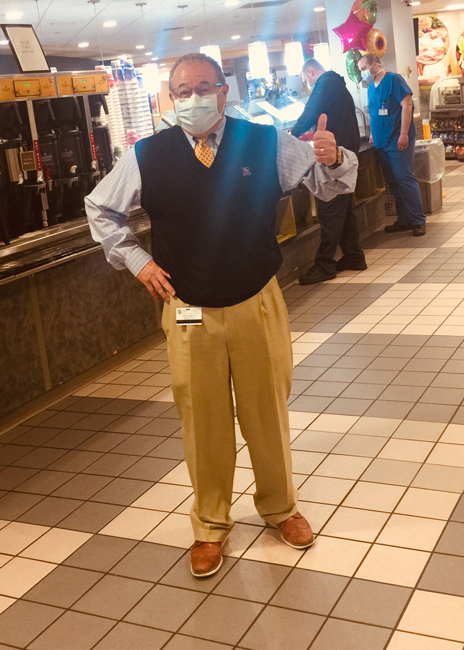

Mike Kasperek, executive chef, displays the Heroes Work Here tribute to essential employees sent by a local church along with food donations.The Dining Room Service

Mike Kasperek, executive chef, displays the Heroes Work Here tribute to essential employees sent by a local church along with food donations.The Dining Room Service

Operating hours at The Dining Room, the hospital’s cafe, remain the same as before March 17 when elective surgeries stopped. “We proposed to administration that we could cut hours and close the cafeteria on weekends, but they decided to keep it going as a convenience,” Almeida says.

Cafe sales have declined to $6,000 a day from $20,000 per day prepandemic. Customer count has dropped to about 1,300 a day from 3,500 a day. Almeida and his team keep a hawk’s eye on production, inventory and food waste. Service has transitioned from largely display cooking with menu items made to order to all grab and go. “We’ve been able to minimize waste so we can be as financially responsible as possible,” Almeida says.

The main kitchen staff prepares menu items and prepackages them daily. “The transformation of menu boards says it all,” Almeida says. “Rather than a long list of menu items and prices, the boards remind customers about wearing personal protective equipment, hand washing and social distancing.”

They position each menu item in the servery. “We had to eliminate as many touch points as possible,” Almeida says. “For example, we have individually wrapped disposable serviceware so customers don’t have to press levers on dispensers.”

As customers walk into the cafe, they find three hand sanitizer dispensers. A sign reminds them to wash their hands. Complying with social distancing requirements, Almeida’s team removed seats so customers can sit at least six feet apart.

The Food and Nutrition department staff inspects donated deliveries in the hospital’s lobby.Staffing

The Food and Nutrition department staff inspects donated deliveries in the hospital’s lobby.Staffing

Almeida’s biggest challenge was and still is to help foodservice employees cope with the situation. “We had to speak with them frequently about the need to remain calm and attentive,” Almeida says. “We are so proud of our 162-member staff.”

Work hours were cut for some employees and others took vacation time. Some employees work only part time. The hospital created a labor pool, so some employees can work in other departments.

“Our team and entire hospital staff have been tested to remain flexible and focused,” Almeida says. “Every day I feel fortunate we have such a strong team.”