The number of branded chain concepts located in nontraditional venues continues to grow. With this growth comes increased awareness and understanding of the particular design and layout challenges that arise from operating in a fraction of the brand's usual space.

These mini versions of their standalone relatives can be as small as one-third of the standard size. The challenge is to remain true to the brand's promise regardless of space constraints on design and layout of equipment.

These mini versions of their standalone relatives can be as small as one-third of the standard size. The challenge is to remain true to the brand's promise regardless of space constraints on design and layout of equipment.

From the preplanning stage to opening day, operators need to address numerous issues. The ultimate goal is an efficient operation that will bring new revenues and profit to the bottom line. To identify issues and solutions, FE&S interviewed a trio of experts: three design consultants who have had significant experience in all aspects of logistics planning, design and build-out of nontraditional units.

The consultants who shared their expertise are John Egnor, owner of JEM Associates in Atlantic City, N.J.; Juan Martinez, principal at Profitality in Miami; and Bill Taunton, president of A.I. Gastrotec Ltd. in Santiago, Chile. Taunton is chair elect of Foodservice Consultants Society International's Americas division (FCSI-The Americas); this is the first time that a member outside of the U.S. has been chair.

Wide-Ranging Opportunities

The list of nontraditional locations is broad, and each type of venue has its own logistical requirements and contingencies. There are food courts in malls, transportation points (airports, train and bus stations, truck stops), hotels, hospitals, nursing homes, college campuses, theme parks and sports arenas. Some locations are foodservice friendly, and others are not. Food courts, for instance, are likely to have the necessary remote storage and prep areas that high-volume operations require. A bus station, on the other hand, likely does not offer these types of spaces, thus introducing additional design challenges.

The host location's physical environment and consumer demographics usually influence the type of restaurant — whether, say, a café or a burger brand. For instance, a decadent burger brand that would fit the bill in a sports arena or a theme park may not be appropriate in a hospital setting. Likewise, a bakery/café is likely not going to appeal to diners at a truck stop.

Speed-of-service objectives will play a role in the brand and menu selection. Waiting for freshly prepared items, for example, may not work well in a busy business-and-industry (B&I) or hospital setting where customers seek service that will allow them to return quickly to their offices or posts.

Before a nontraditional unit is actually built, the project goes through three critical stages: menu strategy, logistics planning and design. The financial success of a nontraditional unit can depend on decisions made during these stages — before the operation even opens for business. Here our panel experts weigh in with issues that the project team must address in these areas and provide their tips for resolving these challenges.

Menu Strategy

Before any decisions take place on the "how," the operator must take a hard look at the menu to determine the "what." Headquarters and franchisees must come to terms with which menu items are a must to protect brand integrity and which items are simply too complicated to prepare in a limited space. A breakfast concept that is known for its 45-minute Dutch pannekoeken must recognize that the dish just won't work in an airport setting. Similarly, a concept that places value on the aroma of a particular menu offering may have to give that up if the smell interferes with the primary business of the host.

The concept's operations manual may restrict some franchisees while others will have a free hand in altering the menu for the location. The operator needs to discuss these factors and make some decisions before bringing in a design team.

Logistics Planning

First, the operator needs to establish the relationship with the host, that is, the owner of the nontraditional venue that will house the restaurant. In many cases, the host will have the last word on most logistical decisions. In some cases, however, if the chain is large enough, the tenant will hold the power.

"The hardest part is integrating chain specs and the requirements of the owner," Egnor says. "That's the first hurdle, ironing out the responsibilities."

Logistics decisions to be made include:

Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC). In most cases, a tenant will not have input into heating or air conditioning other than to assure the systems in place will sufficiently meet the concept's needs. One issue that often needs to be addressed is how the tenant will pay for its share of these expenses.

Ventilation represents a key issue, however. The initial question is who will pay for the installation and upkeep of an exhaust system? In some cases, the operator will want customers to smell cooking aromas. If cooking odor is an issue, how will that be addressed? Regardless, smoke and steam should not escape the exhaust system during the cooking process.

Tip: A catalytic converter in the exhaust system can control cooking odors.

Common Area Maintenance (CAM). This includes costs of the parking lot, external lighting and snow and trash removal. CAM is usually figured on a pro-rata basis. For foodservice operations, trash removal is the most important element of CAM.

Who handles trash removal? It is extremely important that food waste does not sit in the unit for any length of time, as that can result in bad odor, leakage or pests.

Tip: Whether the host or the tenant handles trash, removal should occur on a frequent and efficient basis so customers do not see or smell any messy waste.

Tip: Noncommercial venues, like hospitals, often charge a flat-rate fee; commercial venues may charge a percentage of sales. If the latter, the experts say to be sure that this is a percentage of gross sales. This is often a small percentage, such as 0.1 percent, and is often limited and measured by volume.

Deliveries. Who receives deliveries of food and other items necessary to run the foodservice operation? In a standalone restaurant, the delivery truck can pull up to the back door, and employees can oversee the unloading directly into a storage area that is near the dining area. In a nontraditional unit, however, the receiving and storage areas can be considerable distances from the unit. Security issues may also play a role, particularly for units within airports. Delivery of food and supplies must be handled in a safe, secure and efficient manner.

If storage is significantly limited, more frequent deliveries may be necessary. Operators may incur higher distribution costs for lower minimums and higher frequency, so the more clout an operator has with the distributor, the better. A chain's headquarters will certainly get involved in these discussions.

Tip: Problems can arise when an employee of the host handles food deliveries. This is an area of concern for quality, shrink and food safety issues. The experts say it is best to at least have a restaurant employee present to oversee the delivery process and guarantee standard procedures.

Tip: Operators will also have to negotiate delivery times and frequency with their distributors. Deliveries will have to be timed to also accommodate product deliveries for other businesses.

Remote Storage. How will available storage maintain the integrity, quality and safety of food? Hosts that have a number of foodservice operations in one location will often build a walk-in cooler and dry storage that will serve all units. An operator will need to define how staff will handle the inventory upon delivery to ensure food safety and integrity. Shrinkage can also be an issue, so there should be some method of food security.

Tip: Restaurant staff must have easy access to storage areas in order to replenish supplies during peak times, or the host must provide a flexible and efficient delivery system that fills the operator's needs. Transportation is also an issue. Replenishment of ice, for instance, should be handled in a food-safe manner. To prevent foodborne illness, the buckets staff use to ferry ice from remotely located icemakers to the point of use must be properly cleaned.

Staff Access. How will staff reach the front-of-house or back-of-house areas? The host will dictate security measures such as the issuance of identification badges, access codes or keys.

Tip: Employees should be able to come to work through an employee entrance and leave their outerwear and belongings in a staff area in the back of the house. Ideally, this area will be a good place for breaks as well.

Operating Hours. The restaurant's operating hours generally need to meet the requirements of the host location, though there are exceptions to this. For instance, Martinez notes that a mall near his office hosts a Chick-fil-A unit. Chick-fil-A is not open on Sundays, while the mall is. If a unit has different operating hours than the host location, how will this be handled?

Tip: This will depend on the clout of the tenant. In Chick-fil-A's case, the policy of closing on Sundays is a critical component of their brand integrity. If the host believes the operator will be a profitable partner, accommodations will be made.

The important thing at this stage, the experts say, is to address all of these issues in a document to eliminate any related surprises down the line. Keep in mind that the host makes money from rent and royalties, so they want strong and successful brands. By the same token, operators choose these locations to expand brand awareness and want a relationship that will not break the bank with logistical expenses that eat into profits. An operator's awareness of all the issues and options can provide a solid platform from which to enter the next stage: design of the unit.

Design

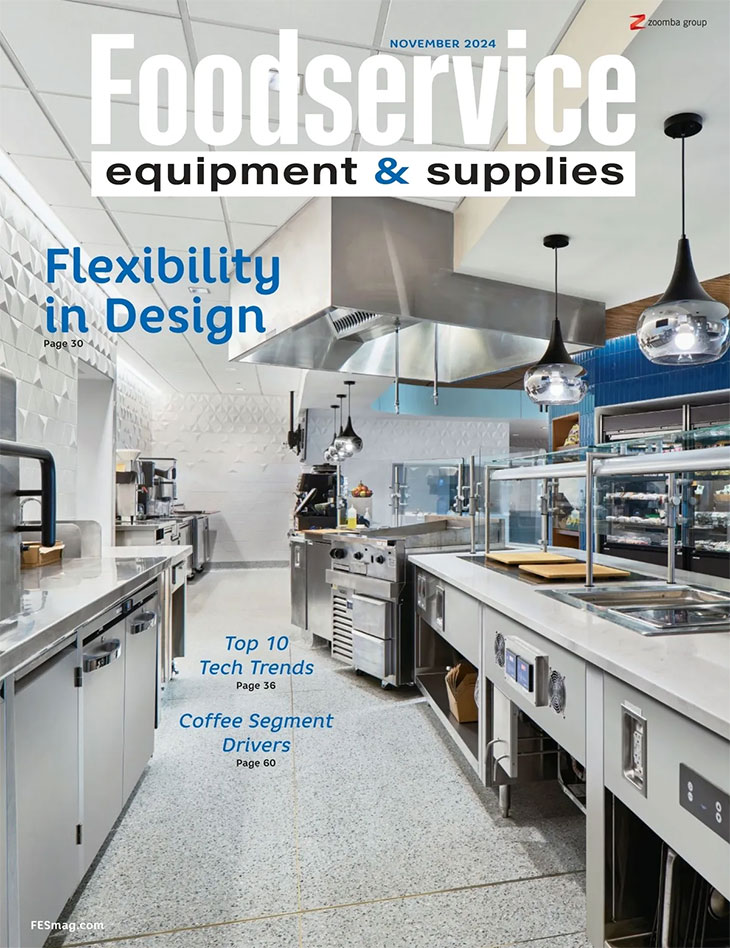

One of the most important considerations when undertaking plans for a nontraditional location is how to keep the design true to the concept's overall brand promise, which is based on a familiar menu and dining experience. Consumers expect a consistent experience regardless of location, but they do understand that they will not have exactly the same experience in a smaller unit as in a standalone restaurant. The menu may not be as extensive, and they may not be seated there. However, they want good, fast service and expect consistency in the menu items that are available.

The brand's menu strategy drives design; all of the equipment is selected to support the delivery of menu items. Since labor is the biggest expense, optimization is the key word for layout. Time and motion studies can aid in the design or space layout. In a small space, there can be no wasted motion slowing down the process or creating bottlenecks in production. Manufacturers will also provide time/motion studies to supplement the services of the design consultant. While the logistics planning stage is key to creating an affordable, safe and efficient environment for the unit, the design stage can be the make-or-break factor in a profitable operation.

Design issues to consider:

Food Preparation. Where staff actually cook the food sets the requirement for all equipment decisions, from type of equipment to layout. Staff may cook some items in front of customers and prepare other items in a commissary and then reheat that food on-site. Some items like sandwiches or salads may be prepared remotely and stored in on-site coolers.

Each method has its own issues. Cooking on-site depends on traffic flow. A unit located in a sports arena can experience a crush of people before games and at halftime; cooking each order on-site would be impossible to pull off. Careful staging of food prep will help manage the process. For menu items staged or fully prepared off-site, the delivery method has to be efficient and preserve food quality at the same time. If this cannot be accomplished, traffic through the number of open stations may have to be limited.

These variables will dictate menu composition. All other equipment and layout choices flow from this primary decision. Careful consideration should be given to the balance between dry, frozen and refrigerated ingredients, as each requires valuable space that would otherwise be allocated to food prep.

Tip: For food prepared in a commissary, location and proximity become critical factors, as is the method of transportation. In some cases, the host will have centralized storage for a number of concepts. The important factor is easy and fast access to inventory as needed.

Equipment. Multiuse technology is the smart choice. Taunton says, in Latin American countries, the installation of European-made multiuse equipment is common. U.S. operators are slower to adopt this technology, however. One equipment vendor estimates that 80 percent of restaurant chains still use gas ranges, griddles and grills in nontraditional locations rather than multiuse equipment.

A number of reasons have contributed to the slow adoption rate here in the U.S. Partly, it is due to human nature; most people are risk averse and see the higher prices and more complex technology as risks they do not want to take. Also, cooking directions and recipes often have not yet been adapted to the newer high-tech equipment. Staff working in the unit may require additional training in how to operate this equipment. Another reason is that specialized one-process equipment (such as a cookie oven) may be used in the traditional location, and policy or contractual obligations may dictate that the same equipment be installed in the new location.

Tip: Duplicating the traditional process in a smaller location may do a disservice to operational effectiveness. Newer multiuse technology will speed up processes and create efficiencies. A combi oven, for example, allows three methods of cooking in one piece of equipment. It has pressureless steam, convected heat and a combination of both. By combining these processes in one, the equipment reduces the amount of square footage necessary for cooking or heating.

The McDonald's clamshell system is an example of nontraditional technology; it replaces a flat griddle and cooks burgers on both sides at the same time so the cook doesn't have to flip the patties. The cooking is also timed for more accurate quality and to address food-safety concerns.

In response to popular menu trends, one equipment vendor is developing a high-speed panini press. The new press cooks a sandwich in less than one minute, shortening the usual six- to eight-minute duration significantly. This will likely be popular with hotels, motels, B&I, hospitals and colleges, where time is of the essence.

On-Site Storage. Some storage in the unit itself, either dry or frozen/refrigerated, will be necessary. The menu drives this need, and the refrigerated units must be optimally laid out for efficient use by staff. A convenient replenishment process must supplement on-site storage. Movement of inventory from remote storage should not hinder the delivery of good service to customers.

One manufacturer is working on a thawing cabinet that can thaw frozen product in six to seven hours – within HACCP guidelines – rather than the typical three days. The cabinet is small enough that an operator can place it in a nontraditional unit. This multipurpose system solves storage needs and shortens prep time. It also allows for reduced loads and more frequent deliveries, a help in smaller locations like airports.

Tip: Often, equipment manufacturers can offer some customization, such as building in storage or adding handles to equipment for easy moving. For example, a place for cooking utensils can be included near where they are used.

Success of design and layout depends greatly on how well the systems and equipment are matched to the needs of the particular venue. Egnor describes the situation at Ravens Stadium in Baltimore where it is possible to have 1,000 customers to serve in 20 minutes. The solution is to group several concepts in one unit. Food must be prepped and ready to cook. Popcorn, peanuts and beer help to satisfy demand.

Egnor says, "As a stadium owner, I want everyone to be fed. Whoever wants something to eat should get what they want." Specifying equipment with overcapacity is usually preferable to underestimating what it will take to serve spikes in customer velocity. Six cash registers help checkout, but as mentioned previously, limiting the number of stations can also help when equipment can't keep up.

This crush is not likely to occur in a venue such as a hospital. While some times may be busier than others, the flow is more likely to be spread out fairly evenly throughout the day and evening. Other venues, however, require careful preplanning. Convention centers have needs that differ from one week to the next, depending on the event. Concepts located on college campuses must accommodate peak traffic when classes are in full session and still turn out a consistent product for students and staff during summer or holiday periods. Convenience stores depend on speed. And each venue will have different design and layout requirements.

Once all of these issues are resolved, the unit is ready to be built. If all the t's are crossed and the i's dotted by this time, this stage should proceed with ease.

There's one thing our experts agree upon: If the nontraditional location stands to increase profits for the concept owner as well as the host, each party should consider all avenues that will make it a successful venture and a win-win for tenant and host.

The Depths of Nontraditional Foodservice Design

“It’s a different world south of the border,” says Bill Taunton, president of A.I. Gastrotec Ltd. in Santiago, Chile. Taunton has clients in a number of Latin American countries who commission him to design units for nontraditional locations. He says that most countries want to attract the large U.S. chains like Papa John’s and China Wok. As in the U.S., chain units tend to be located in retail and noncommercial venues, and this trend is growing. One particular type of nontraditional operation is unique, however, and presents challenges for Taunton that his U.S. counterparts do not face.

Mining of gold, copper and silver plays a significant part in the economies of Chile and Peru. The companies running these open-pit or below-ground mines have a legal obligation to feed the workers hot meals. And below-ground mines in particular provide some interesting challenges. Taunton describes a typical situation: “It takes the workers an hour to get to work in the tunnels and an hour to get out. The tunnels can be 2,700 feet under the earth. Obviously, they can’t come out for lunch, it would take three hours.” The solution? Underground dining rooms.

A main kitchen produces food that is served in a dining room. Since using gas would be dangerous, all equipment is electric. Glasses and dishes are washed in water that is transported to the site, but pots and pans are hauled to the surface to be washed. Water tanks are reserved for fresh water and for wastewater. These, along with any other waste, have to be hauled to the surface to be discarded properly. Each of these tasks requires careful planning so that food and location safety are assured. Delivery also has its own challenges. Everything has to be transported from ground level to the depths.

“The tunnels are like Swiss cheese,” Taunton says. The workers get to know their way around, and chances are, they always know where the dining room is operating and a hot meal awaits.