It’s no longer the cost of labor alone that keeps foodservice operators awake at night. It’s also the fact that labor has become a scarce commodity. These factors have foodservice operators continually exploring ways to better manage this part of their business. For multiunit operators, though, the challenge grows exponentially as they try to properly manage labor across a portfolio of similar, yet not identical, locations.

Ignacio Goris, Labor GuruWhen tackling such a challenge, business leaders must first understand the differences between each facility, including their designs, customer base and more. Four of the most common approaches to setting labor targets are activity-based, empirical, benchmarking or financial. Let’s take a quick look at each.

Ignacio Goris, Labor GuruWhen tackling such a challenge, business leaders must first understand the differences between each facility, including their designs, customer base and more. Four of the most common approaches to setting labor targets are activity-based, empirical, benchmarking or financial. Let’s take a quick look at each.

Activity-Based Labor

This represents the most complete and precise way to manage labor. This approach quantifies all the activities that foodservice personnel perform. The process involves documenting and performing time and motion studies of all activities: service; nonservice variable tasks such as food prep and dishwashing, as well as fixed labor activities, such as the steps that come with opening and closing the restaurant. When quantifying these activities, take into account the necessary time to start up, shut down and clean the relevant pieces of foodservice equipment. It’s also important to note time changes on specific activities that vary based on the layout from one location to another. For example, in the case of a multiunit operator, not every dining room will be the same size, which means it will take different amounts of time to clean this space.

After accounting for all the times that coincide with the individual activities, the next step is to calculate the total labor a given foodservice location will require. Documenting all of this, including the differences in equipment, will determine how labor needs will vary by location.

This objective approach allows operators to evaluate individual equipment or layout changes together or separately. A layout that requires the same number of people, regardless of whether it’s during peak or nonpeak periods, will only be truly efficient during the busiest times.

Benefits of activity-based labor systems include ease of updating the labor needs for a prototype or an entire system. Upon completing the initial work, it can become easier to update the guidelines when changes occur to operating, sales or facility parameters. Another benefit is the ability to perform sensitivity or what-if analysis related to layout, equipment or process changes as it relates to labor impact. The con of this approach is that it requires more time and effort to complete — not only to document tasks, but also each store’s physical characteristics, including equipment package, layout style and facility size.

Empirical Labor

This approach also requires observations at the restaurant level, but those become more empirical and high-level in nature. Instead of measuring every activity, management selects well-running venues of different styles. By work sampling labor use at these different restaurants during different periods, you can calculate how many people are necessary by station and by volume. From this information the team can derive productivity metrics by position, volume and layout style. Use a similar approach to document fixed activities such as opening and closing the restaurant, and nonservice variable activities such as food prep. Using that information can help when modeling the labor necessary to operate a restaurant. This represents an approach similar to the activity-based one since actual field observations are performed but with less inputs.

Using the empirical labor approach will yield, in the short term, similar outputs as the activity-based labor approach. This empirical labor approach captures productivity for an observed set of conditions (location, time and volume). Also, it takes less time to convert the observed labor into guidelines, shortening the process. The downside to this approach is that it requires specific observations of each unique layout or equipment package to measure the real labor differences from one location to the next. Finally, given that the empirical approach only generates a snapshot at a given point in time, it will not provide the ability to update targets based on changes to the operating parameters.

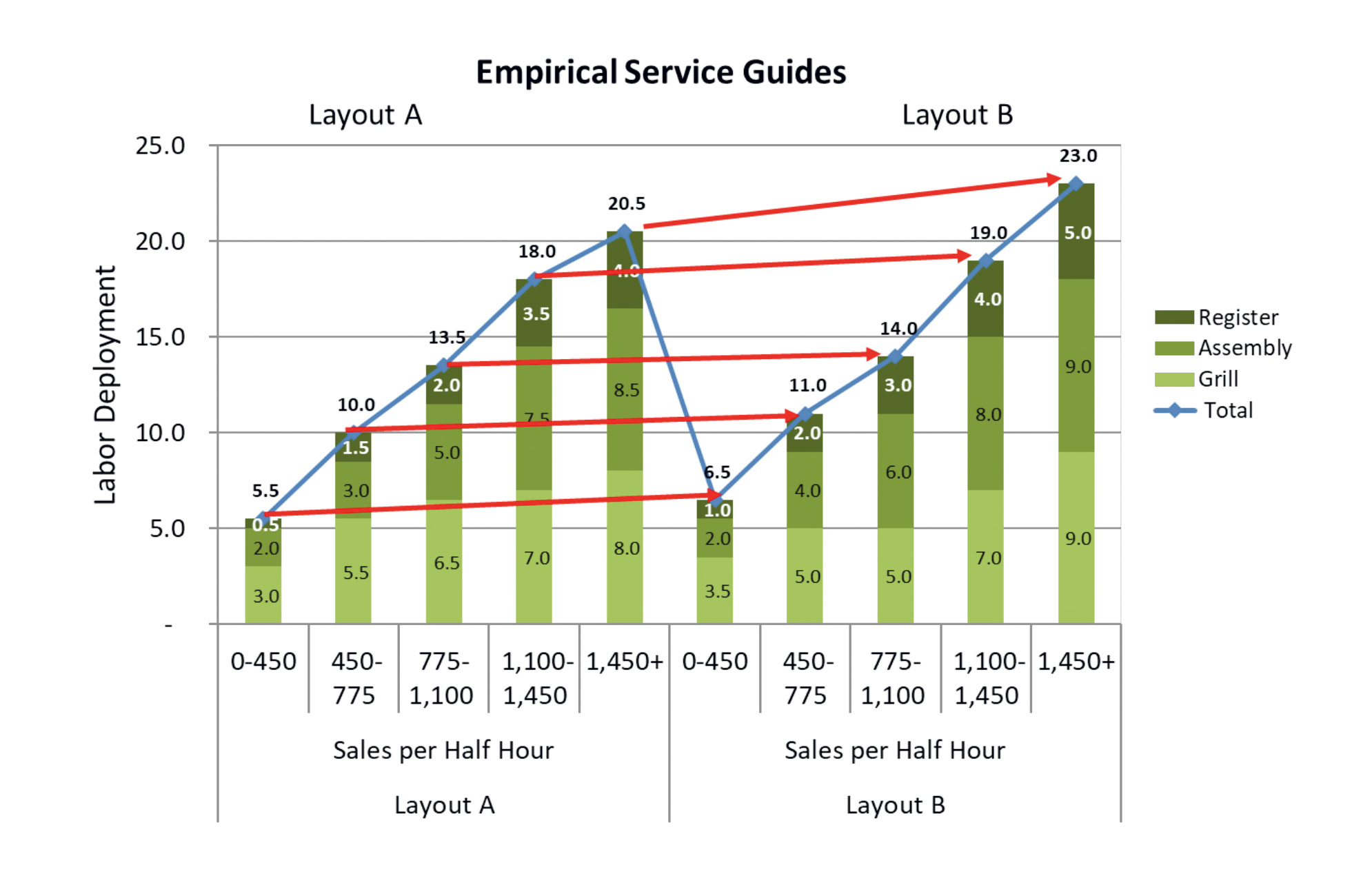

The empirical labor approach captures productivity for observed conditions and layouts as shown in this chart.

The empirical labor approach captures productivity for observed conditions and layouts as shown in this chart.

Benchmarking Labor

This approach works well for multiunit operators that track and compare the performance of their own stores. Oftentimes, these operators will position their most efficient locations as the gold standard within the chain to establish productivity targets for the rest of the locations.

Part of this process includes categorical benchmarking and having to group each layout style and equipment package to compare labor usage. If the labor differs based on layout or equipment package, that location requires a separate grouping to ensure an accurate comparison. Scatter plots can help establish productivity for varying activity volumes. For the daily targets, create a scatter plot of sales or other relevant metrics such as guest counts or actual meals served versus labor hours used. Then calculate the trend line of the best 70 percent to 80 percent of performers.

That trend line becomes the labor target for a given restaurant group. Repeat the same exercise for other layouts or equipment packages that have unique labor characteristics.

An additional benchmarking exercise that follows a similar methodology but for peak half hours will help determine peak productivity for service labor guidance. In this instance, maintain the original restaurant groupings. Then develop a scatter plot between peak half-hour volumes (sales, guests, entrees, etc.) vs. total staff deployed during those half hours. The last step, once again, is to develop the trend line for the top

70 percent to 80 percent of the system.

This approach can make it easier to convince people internally that targets are realistic and achievable given that targets are based on the best-performing units in the chain, while taking into account their operational differences. The con of the approach is that we don’t know if the top performers are doing as good as they can as it relates to labor efficiency and customer service; we only know that they are doing better than the others.

Financial Budget

This represents the most common and simple approach that many concepts use. Why do so many concepts use it? This approach pairs with the operator’s financial targets. The financial model does not typically take into account the differences between layout styles or equipment packages from one location to another. Every location, regardless of design or equipment package, will receive the same financial goals based on a sales target. On very rare occasions, an operation applying this approach will provide different financial targets based on layout type.

The benefit of this approach is that locations that follow the budget will meet their financial objectives, even if sales are lower. This usually translates into profitable locations. The downside of the financial budget approach is its failure to consider the unique attributes of a given location. In this instance, squeezing labor out of certain days may achieve financial goals, but it may not result in the guest service necessary for long-term success. So the net result becomes lower sales. Financial budgets also tend to allow for more labor than necessary on busy days and not enough labor on slower days.

A way to counteract this is to ensure the percent of sales budget includes both fixed and variable labor costs.

All four labor control methods have advantages and disadvantages and it is important for a company to select the right way to do this; short term and long term.