Oftentimes in the restaurant industry, we find ourselves laser-focused on the task at hand. It’s a good idea to lift our heads, on occasion, and take a look around at other industries as they can teach us plenty, too. One specific story that piqued my interest as of late is the saga surrounding WeWork.

The co-working company was successful and on the rise in 2018; it would eventually hit a $47.5-billion-dollar valuation in January 2019. By all accounts, many people felt there was a bright future for co-working companies like this one. This led WeWork to begin growing very quickly, looking for locations in major cities across the globe. The company sought support from blue-chip investors such as Benchmark as well as major Wall Street banks, like JP Morgan Chase, as this Reuters story notes. WeWork’s leadership really believed that if the company continued to build them, that organizations and individuals would continue to come to their shared office spaces.

Unfortunately for WeWork, after spending so much money to build out this multicontinental network, the global market for office spaces took a dive. WeWork did, indeed, build it but the customers stopped coming. As of early November (of this year?), WeWork filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

What does this cautionary tale have to do with designing restaurant prototypes? Well, as it turns out, plenty.

When restaurant designers and decision-makers think about building a new prototype for their brands, oftentimes, their instincts lead them to taking an approach that yields big and flashy results. This comes from an often misguided goal of trying to position the new prototype to have the capacity to do 200% more business than the current prototype. But that may not be the best approach, as it often leads to empty spaces in the restaurant or overspending in construction costs.

When developing a new restaurant prototype, don’t let feelings be the basis of your design. Rather, use data to drive the design. Most restaurant concepts will have historical performance data such as past sales information, ranging from hourly to weekly, relative to the size of restaurants, number of seats and tables, revenue mix, etc. Let this data be your guide when projecting how the business may perform in the future.

For example, if the current average unit volume of a concept’s portfolio is $2.5 million, then building a facility to do $7 million in annual volume may be an exercise in overbuilding, overspending, and other overabundances.

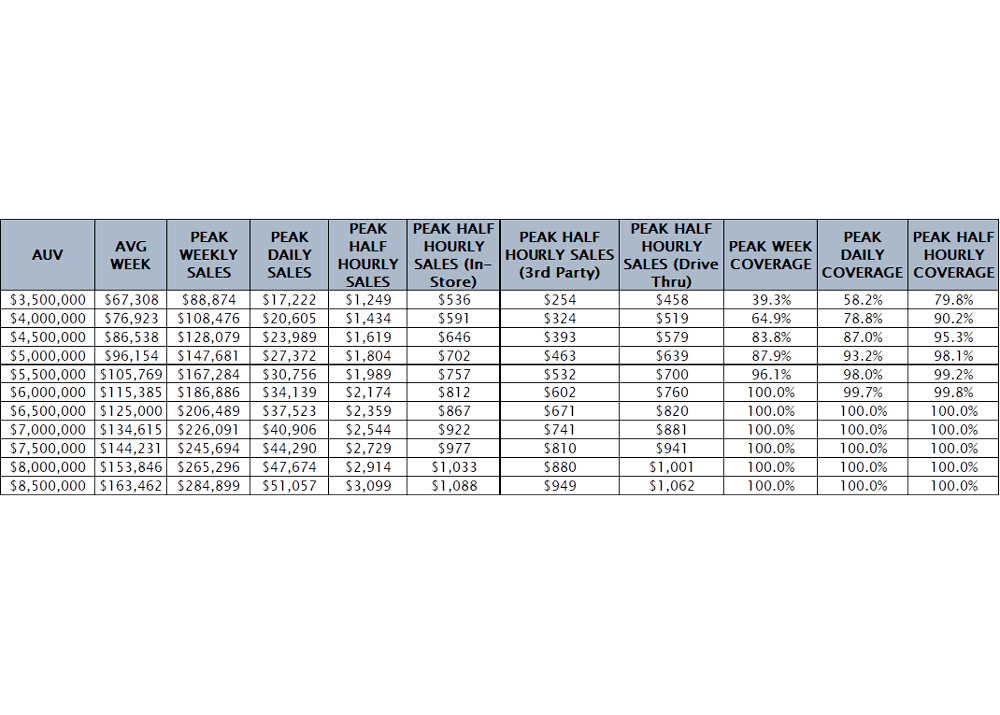

Looking at the following data table, a concept may be able to discover relationships among the different sales periods, identifying point estimators for expected peak periods. The table below is an example, highlighting for different annual sales (AUV), what some of the expected busier weeks, days, and half-hours will be:

Letting data like this guide your decision making can help prevent overspending on larger-than-necessary builds, especially if a concept aims to develop a prototype that can achieve 200% more than current sales levels.

Combine this type of data with cook times, item velocities, revenue-center goals, party and transaction sizes, and other assumptions for the new prototype to calculate the resources necessary to execute during expected peak periods. This will provide minimum, and to a certain degree, maximum, design constraints to be cognizant of as the new building takes shape. The number of tables and seats drives the dining room size, the number of (pieces of) line equipment drives the line size, and the size of the storage areas, from coolers and freezers to dry, drives the size of the back of house.

With data, and the right use of data, designers can develop the optimum size, and flexibility, of the new prototype. The designer can add flexible seating in the dining room or additional space in the front-of-house, or kitchen, for critical areas that are nearing their capacity. Whichever the case may be, data can help curb the enthusiasm for overabundance when it comes to designing new buildings, especially with how costly constructing a new building has become.