Singer Equipment Company earned the FE&S 2023 Dealer of the Year award by dramatically transforming its business in the past decade.

Through a combination of attracting and nurturing talent, showing a willingness for creative thinking, and astutely identifying like-minded companies for acquisition, the Elverson, Pa.-based company has grown into the fourth largest FE&S dealer in America, per the FE&S 2023 Distribution Giants study. The company’s astute decision to focus on complex, multiunit customers that needed differentiated products and differentiated services — no cash-and-carry, no showroom services — was a game changer. To learn how Singer Equipment did this, first you should understand its guiding philosophy.

Singer Equipment boasts a deep well of executive leaders. Pictured here: Eric Santagato, vice president of distribution sales; Fred Singer, president and CEO; Seth Feldman, CFO; Morgan Tucker, vice president of marketing; and Mark Woolcock, executive vice president. Photographs taken at Fearless Restaurants operation Autograph Brasserie. Fearless Restaurants is a multiconcept operator owned by Marty Grim.

Singer Equipment boasts a deep well of executive leaders. Pictured here: Eric Santagato, vice president of distribution sales; Fred Singer, president and CEO; Seth Feldman, CFO; Morgan Tucker, vice president of marketing; and Mark Woolcock, executive vice president. Photographs taken at Fearless Restaurants operation Autograph Brasserie. Fearless Restaurants is a multiconcept operator owned by Marty Grim.

The Backstory and the SPARK

In 2020, Singer Equipment set out to build a company-wide culture statement that would build on the values that drove the organization. As a third-generation family business more than a century old, Singer Equipment had already weathered countless changes in the market and had a reputation as a reliable supplier in the foodservice industry. But president and CEO Fred Singer and his leadership team understood the need to look ahead, not back. The key to doing so was defining their values for everyone they employed and came into contact with. They wanted something that would spell out, and define, their path forward. Though the company’s values had changed very little over 102 years, characterizing their values turned out to be a tall order. Defining something that has always been intrinsic proved quite the challenge, akin to writing the corporate origin story that would survive the test of the next 100 years. “We brainstormed and came up with literally 700 words that described the attributes we wanted to be able to promise all of our partners — customers, vendors [and] coworkers — that we would deliver on,” says Fred Singer. “And we stripped it all the way down to 5.” Thus was born the Singer SPARK (Service-driven; Professional; Accountable; Responsive; and Knowledgeable).

Those five words don’t simply color the way Singer Equipment does business. They paint the whole picture, defining every single interaction for Singer Equipment’s employees and partners. The words are now printed everywhere in the company’s 180,000-square-foot offices and distribution center. They’re on coffee cups, walls and shirts in Singer Equipment’s offices up and down the Eastern Seaboard. If you can’t embrace and embody those five values, the company wishes you the best but is simply not interested in working with you. “There are people who are amazingly special,” says Fred Singer. “But if they don’t fit the five we settled on, it’s not going to work.”

All this may sound like some kind of empty corporate self-improvement nonsense, but Singer Equipment lives by it. Every single one of its 800-plus employees — whether an executive, a human resources director or a customer service rep — internalizes and understands what these values mean on a granular level. They mean telling the truth, even when the truth is unpleasant — standing behind every piece of equipment sold and taking responsibility if things go wrong. And most importantly, the Singer SPARK absolutely demands the development and sustainment of long-term relationships with customers, vendors and co-workers. “The SPARK is a separator that shows how we think about our people and what we want to do for them,” says Seth Feldman, Singer Equipment’s chief financial officer. “And it makes Singer a great place to work.”

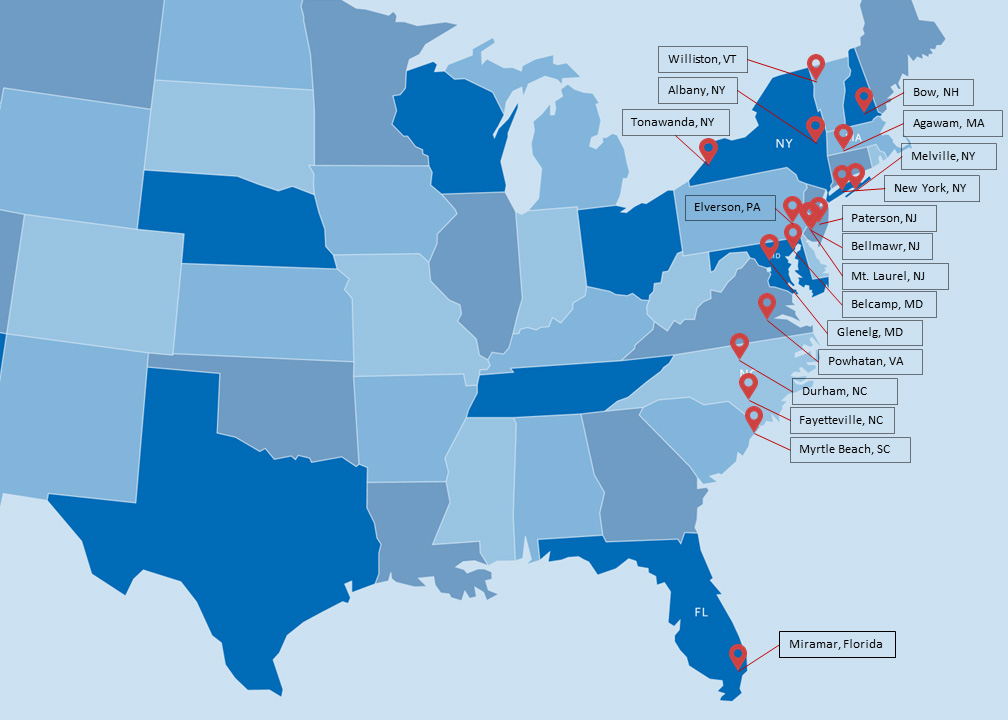

Singer Equipment’s territory acquisitions have bolstered Singer Equipment’s presence along the eastern U.S. The company now has a total of 18 locations.

Singer Equipment’s territory acquisitions have bolstered Singer Equipment’s presence along the eastern U.S. The company now has a total of 18 locations.

Singer Equipment’s Territory Acquisitions Timeline

Over the past 12 years, Singer Foodservice Equipment and Supplies Company has made 6 strategic acquisitions.

A brief timeline summarizing these deals:

- 2011: M. Tucker

- 2017: Ashland Equipment

- 2017: Facilities Services

- 2019: EVI

- 2021: Thompson & Little

- 2022: Kittredge Restaurant Equipment

Walk the Talk

What does this look like in action? Say a new convection oven installed in a restaurant isn’t functioning properly: Singer Equipment will replace it, even if the manufacturer says the unit is out of warranty. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when lead times were badly extended and Singer Equipment found itself in the constant position of delivering bad news to customers, it did so truthfully every time, even when those conversations had major implications for customers’ projects. The goal was not to simply sell things, but rather to focus on helping people manage their businesses, lower their costs and find products that solve their problems. By keeping the focus on long-term relationships and not transactions, Singer Equipment nurtured partnerships, which led to repeat business that lasted long after the pandemic was over.

Fred Singer president and CEO “Our acquisition strategy is to focus on the geographies that we prioritize, the types of customers that we serve and the culture of the organization.”

Fred Singer president and CEO “Our acquisition strategy is to focus on the geographies that we prioritize, the types of customers that we serve and the culture of the organization.”

“Every single touch point that a salesperson has with the customer is put through the Singer SPARK,” says Eric Santagato, vice president of sales. “From the time that they place an order; to the time we pick up the phone; to the time it gets on the truck; to the time it’s delivered — it’s in the way the driver treats the person receiving the order, so that the customer can walk away saying, ‘That’s a great company that I want to continue to work with.’” The company’s knack for finding and keeping large multiunit customers who gravitate toward a more relationship-based approach allows it to anticipate the changes to the foodservice industry. Singer Equipment unearths these customers by doing its homework and asking these questions: Were they in a longstanding relationship with their previous supplier? How do they treat their current suppliers? What reputation do they have in the vendor community? Then, when meeting the people and discussing Singer Equipment’s values, they watch closely to see how they respond. At that point, it’s fairly obvious whether they are sympatico. “Our industry is littered with some pretty forward-speaking people,” says Jeff Mackey, president of Singer Kittredge. “But when we meet with customers, they say, ‘You know, you guys listen more than you talk.’” Singer Equipment acquired Kittredge Restaurant Equipment — another long-standing, family-owned company, based in Agawam, Mass., in 2022.

Mark Woolcock, executive vice president, “I spend a lot of time talking about plans and strategy.”Singer Equipment’s principled approach may sound old-fashioned. Obvious, even. But in a tough sector where restaurateurs once saw dealers as adversaries, often comparing them to used-car salesmen, simple things like responsiveness were not a given. Singer Equipment saw which way the wind was blowing and successfully tapped into something honest and true: A business built on trust is built to last. “Nothing that we’re doing is unreasonable or novel,” says Morgan Tucker, vice president of marketing. “We simply take care of our people and do the right thing.”

Mark Woolcock, executive vice president, “I spend a lot of time talking about plans and strategy.”Singer Equipment’s principled approach may sound old-fashioned. Obvious, even. But in a tough sector where restaurateurs once saw dealers as adversaries, often comparing them to used-car salesmen, simple things like responsiveness were not a given. Singer Equipment saw which way the wind was blowing and successfully tapped into something honest and true: A business built on trust is built to last. “Nothing that we’re doing is unreasonable or novel,” says Morgan Tucker, vice president of marketing. “We simply take care of our people and do the right thing.”

This anachronistic modus operandi has not only attracted the right partners but also it has drawn the best talent to work in its offices from unlikely places, which in turn freed these individuals to play to their strengths. “We’re not afraid to bring talent into the organization just because they don’t have foodservice equipment experience,” says Feldman. “We want the best talent in the organization to move the company forward.” Before joining Singer Equipment in 2017, Santagato, for example, was a sales manager at the solid waste company Republic Services. “It was just straight garbage and recycling all day long,” he recalls. “I had never even heard of the foodservice industry.” But in Santagato, a former college football quarterback, Fred Singer sensed something — this guy gets it! — and before long, Santagato was charged with building the company’s sales team and merging the entire business into a single, unified salesforce. Whereas before, the company had two primary distribution centers and customer service departments operating separately in New York and Pennsylvania, Santagato streamlined both departments. And where the sales teams in multiple regions once had their own sales meetings, now the entire team of 85 people is in the same room together. “I don’t have to roll out things twice — or more,” says Santagato. “At the sales leadership level, they’re all connected. The person doing sales in Brooklyn knows the person in Lancaster, Pa. That’s allowed us to move forward faster. And Fred allows us to take risks. Those chances to say, ‘Try it. Give it a shot. Let’s see if it works.’”

Seth Feldman, chief financial officer, “We’re not afraid to bring talent into the organization just because they don’t have foodservice equipment experience.”Singer Equipment has also become known in the industry for its surprising transparency with vendors, which means sharing strategic plans with partners in the supply chain and customers. Fred Singer explains, “We’re trying to be more tightly integrated with our critical vendors than maybe a traditional dealer is — one that might see things differently from their own strategic purposes. So it’s critical for me to understand the strategy and direction of my vendors: What customer segments are they trying to approach? How do they see their products? What geographies are critical for them? And it’s important that they understand what we are trying to accomplish. If you do that right, we can win together.” Those are the kinds of counterintuitive moves that have fueled Singer Equipment’s steady growth.

Seth Feldman, chief financial officer, “We’re not afraid to bring talent into the organization just because they don’t have foodservice equipment experience.”Singer Equipment has also become known in the industry for its surprising transparency with vendors, which means sharing strategic plans with partners in the supply chain and customers. Fred Singer explains, “We’re trying to be more tightly integrated with our critical vendors than maybe a traditional dealer is — one that might see things differently from their own strategic purposes. So it’s critical for me to understand the strategy and direction of my vendors: What customer segments are they trying to approach? How do they see their products? What geographies are critical for them? And it’s important that they understand what we are trying to accomplish. If you do that right, we can win together.” Those are the kinds of counterintuitive moves that have fueled Singer Equipment’s steady growth.

As it amassed a crew of principled employees across the entire enterprise, opened the lines of communication between vendors and clients, and strategically acquired compatible businesses, the company reports its annual revenues grew to $699 million by the end of 2022. “Our acquisition strategy is to focus on the geographies that we prioritize, the types of customers that we serve and the culture of the organization,” says Fred Singer. “These filters screen out the vast majority of companies we see.” In doing so, Singer Equipment became one of the largest suppliers of commercial kitchens in the New York/Philadelphia/Washington, D.C., marketplace, with a presence felt in markets along the East Coast from Miami to the Canadian border.

Future-Forward Thinking

Eric Santagato, vice president of sales, “Every single touch point that a salesperson has with the customer is put through the Singer SPARK.”The seeds for Singer Equipment’s recent rise were planted in 1993. Fred Singer, an even-keeled Yale graduate who had recently cut his teeth at the famed Boston Consulting Group, finally joined the family business, which had $22 million in annual sales volume at the time. Almost immediately, the self-described “gentle optimist” perceived a sea change coming in the industry. “My sense was that the customer of the future was going to be a much larger company, a more complex company, a more professional company,” says Fred Singer. “And they were going to be looking for the same attributes in their suppliers.” He theorized that if Singer Equipment didn’t shift its focus, the company would quickly become irrelevant. And the best way to grow market share with the right type of customer in the future, he surmised, would be to become the best relationship-based supplier.

Eric Santagato, vice president of sales, “Every single touch point that a salesperson has with the customer is put through the Singer SPARK.”The seeds for Singer Equipment’s recent rise were planted in 1993. Fred Singer, an even-keeled Yale graduate who had recently cut his teeth at the famed Boston Consulting Group, finally joined the family business, which had $22 million in annual sales volume at the time. Almost immediately, the self-described “gentle optimist” perceived a sea change coming in the industry. “My sense was that the customer of the future was going to be a much larger company, a more complex company, a more professional company,” says Fred Singer. “And they were going to be looking for the same attributes in their suppliers.” He theorized that if Singer Equipment didn’t shift its focus, the company would quickly become irrelevant. And the best way to grow market share with the right type of customer in the future, he surmised, would be to become the best relationship-based supplier.

At the time Singer Equipment was making these changes, the company had no idea how much of a mega trend consolidation would become within the foodservice industry. Thanks to an influx of capital from public markets and private equity, dealers, factories and other foodservice industry segments have experienced significant consolidation in recent years. “As dealers, we serve both manufacturers and end users,” Fred Singer notes. “As both manufacturers and end users consolidate, their needs change, and both will have their needs more directly met by a larger dealer. Customers want one supplier that can scale with them, providing the geographic coverage and the array of services they need to simplify the challenges of expanding their company. That is the imperative driving consolidation.”

Today, adjusting to the unstoppable force of consolidation sounds like a no-brainer. It was preparing for it that involved a major shift in the company’s philosophy.

Henry Singer, Fred Singer’s father, who ran the company from 1955 to 1999, was a natural salesman gifted at finding customers who needed the foodservice equipment housed in his warehouse and selling it to them. Fred, however, suggested a more methodical approach. Rather than fill the warehouse with products that might sell and then seek out buyers, why not flip the equation? Decide what type of customer Singer Equipment wanted to serve, learn what products and services that customer needed to be successful and change Singer Equipment’s warehouse inventory to reflect that? The 2005 addition of Mark Woolcock, a draftsman by trade and former competitor who shared Singer’s forecast regarding consolidation, balanced the boss’ bold vision with cold, hard strategy. “He’s looking so far down the road, like, here’s where we’re going to be in seven years,” says Woolcock, now Singer Equipment’s executive vice president. “I spend a lot of time talking about plans and strategy.”

The big next step involved strategically identifying companies for acquisition. When business acquisitions fail to create value, Fred Singer notes there are usually two reasons why. One is bad strategy, and the other is a poor cultural fit. “Studies show most acquisitions don’t add value, so you’re betting against the odds every time you do one,” Fred Singer says. But if his team could harness Singer Equipment’s century of name recognition and connections to identify other geographically compatible companies that share similar culture, Fred Singer reasoned, he could beat the odds. Then they’d have something.

Morgan Tucker, vice president of marketing, “I got lucky enough to inherit Fred Singer.”This played out in 2011 when Singer Equipment acquired M. Tucker Company. “We had a lot to learn about integrating companies,” Woolcock recalls. But the acquisition of the venerable third-generation foodservice equipment company gave Singer Equipment a greater stronghold in the New York market. And by respecting M. Tucker’s depth of talent and integrating the two companies’ knowledge and insights, it didn’t take much to enfold M. Tucker’s like-minded employees into the Singer Equipment cocoon.

Morgan Tucker, vice president of marketing, “I got lucky enough to inherit Fred Singer.”This played out in 2011 when Singer Equipment acquired M. Tucker Company. “We had a lot to learn about integrating companies,” Woolcock recalls. But the acquisition of the venerable third-generation foodservice equipment company gave Singer Equipment a greater stronghold in the New York market. And by respecting M. Tucker’s depth of talent and integrating the two companies’ knowledge and insights, it didn’t take much to enfold M. Tucker’s like-minded employees into the Singer Equipment cocoon.

“I got lucky enough to inherit Fred Singer,” says Morgan Tucker, whose family made the decision to sell M. Tucker. “I’m deeply grateful to all the decisions that my father [Stephen Tucker] made to part with the business to choose such a thoughtful and kind steward.” Morgan Tucker started at Danny Meyer’s Union Hospitality Group, and after transitioning to the dealer world, was named the FE&S 2012 Dealer Sales Representative of the Year.

The company’s measured but ambitious business plan accelerated in 2016 when it brought in Seth Feldman, a former CFO at eBay Enterprises. On paper, the New York native’s pedigree, which involved two decades of experience with Fortune 500 companies, made him an unlikely candidate to pair with a homegrown family company like Singer Equipment. But Feldman had grown up in a privately owned family business called Tri-Supreme Optical, and Fred Singer saw in him another kindred spirit who understood what Singer Equipment was trying to do. Feldman, who now oversees all operations in Singer Equipment’s warehouses, as well as its trucking, delivery and IT departments, helped change the way the dealer looked at financial performance, cash flow management, vendors, customers, employees — basically everything.

“Fred allowed me to have the influence from the chair of the CFO to drive the company to be more efficient and make better financial decisions, so we could reinvest the dollars back in,” says Feldman, who helped the then-$250 million company deploy incremental capital to buy companies that fit Singer Equipment’s strategic vision — and walk away from deals that simply wouldn’t make sense. Feldman commends Fred Singer for not only having the vision to change the company but also for showing the bravery and patience to actually make it happen at a thoughtful pace. “That’s not an easy step to take for a third-generation CEO in a 98-year-old business,” says Feldman. “Absolutely he could have made baby changes. These were not baby changes.”

During Feldman’s seven years at Singer Equipment, the company has pulled off five acquisitions. One of them was Thompson & Little, a mid-sized dealer based in Fayetteville, N.C. When Thompson & Little’s third-generation president, Drew O’Quinn, was initially approached by Singer Equipment in 2019, he was impressed by Fred Singer’s and Feldman’s willingness to listen. “Fred and Seth said, ‘We’re purchasing you because of your history, because of your culture, because of everything you bring to the table,’” says O’Quinn. “And they were true to their word.” His entire team remained after the acquisition.

Drew O’Quinn, president, Singer T&L, “Everybody here has a voice and an opportunity to lead.”Shortly after Thompson & Little’s seamless integration into Singer Equipment, O’Quinn found himself fascinated by the company’s uncanny ability to get his crew on the same page. The Singer SPARK was always in the air, organically transmitted from veterans to newcomers, ensuring that as the company grew and welcomed new groups under the Singer Equipment umbrella, they would all move in the same direction, regardless of division. At a recent meeting, O’Quinn reports that when a human resources director spoke up with a suggestion to look at an issue from a different angle, the team was quick to explore it. The meeting turned on a dime. “We ended up going with the idea,” says O’Quinn, who runs the Singer Thompson & Little division much like he did before. “I thought that was really impressive. Everybody here has a voice and an opportunity to lead.”

Drew O’Quinn, president, Singer T&L, “Everybody here has a voice and an opportunity to lead.”Shortly after Thompson & Little’s seamless integration into Singer Equipment, O’Quinn found himself fascinated by the company’s uncanny ability to get his crew on the same page. The Singer SPARK was always in the air, organically transmitted from veterans to newcomers, ensuring that as the company grew and welcomed new groups under the Singer Equipment umbrella, they would all move in the same direction, regardless of division. At a recent meeting, O’Quinn reports that when a human resources director spoke up with a suggestion to look at an issue from a different angle, the team was quick to explore it. The meeting turned on a dime. “We ended up going with the idea,” says O’Quinn, who runs the Singer Thompson & Little division much like he did before. “I thought that was really impressive. Everybody here has a voice and an opportunity to lead.”

Prior to of the acquisition of Kittredge Restaurant Equipment, Mackey spent eight months working with Fred Singer to prepare for the big move. “Fred and I shared the same paths through foodservice, and his values were identical to ours,” says Mackey. “In those eight months, I became more Singer than I was Kittredge. I had to believe this was

the right place — not only for me but [also] for the other 99 people that we work with. And I did. So selling that idea to them wasn’t hard.” (Fred Singer calls the process “re-recruiting.”) A year into the deal, Singer’s Kittredge division has expanded through New England and New York State, and Mackey says he has people knocking at their door from competitors wanting to come work at Singer Equipment.

The fact that Singer Equipment managed to enfold these companies, along with a handful of others, into their world — without losing any of the cohesive culture — is a testament to careful research. “If I don’t believe the people of the company will be happy and successful working within our culture,” says Fred Singer, “there’s no point in doing the deal.” In other words, he doesn’t force-feed the Kool-Aid to those that won’t like the taste.

Synergy Realized

And what about the elusive synergy that all too often fails to materialize when companies join forces? At Singer Equipment, synergy is more than a buzzword — it’s a reality. “At Kittredge, I was fortunate enough to have 15 of the best salespeople in New England,” says Mackey. “Under Singer, we’ve got 100 or 200 of the greatest salespeople on the Eastern Seaboard.”

Three of Singer Equipment’s VPs: Don Oleski, vice president of technology; Bob Meyer, vice president of procurement; Greg Consoletti, vice president of operations

Three of Singer Equipment’s VPs: Don Oleski, vice president of technology; Bob Meyer, vice president of procurement; Greg Consoletti, vice president of operations

Much of the company’s development and education comes from within. “We have all these different resources and people that have been with the company for over 30 years,” says Santagato. “Think about all the knowledge that those folks can share. The more I spend time with more people, the more I learn.” And though the company’s sales leaders are competitive, Santagato says they’re constantly encouraged to share best practices — and they do. He cites the sales leadership team’s weekly call, in which reps from, for example, the Philadelphia market, share their experience with their counterparts in New Jersey markets. “We’re able to leverage each other better than we ever have,” he says. “It totally works when you have the right people that are receptive.”

With Singer Equipment growing steadily, carefully and organically, when CFO Feldman says he envisions the company as the next foodservice equipment and supplies dealer to exceed $1 billion in annual sales, it’s not a stretch. “That’s something that I see us doing here in the short to medium term,” he says. “I think we will continue to expand our geographic footprint. I don’t necessarily know if there is a moment in time where we’re too big, but I don’t think we’re anywhere near that at the moment.”

Fred Singer plays his cards slightly closer to the vest, preferring to frame the future in terms of his favorite subject: relationships. “Our goal is pretty straightforward,” he says. “To create a company where everyone who comes in contact with our stakeholders, our employees, our customers our vendors — everybody — leaves the experience of working with Singer as an enriching experience.” It’s an ambitious aim, but so far, so good.

Five Mistakes

Here are five common errors that companies make, according to Fred Singer.

Members of Singer Equipment’s leadership team (clockwise from top): Marc Fuchs, sr. vice president, Singer M. Tucker; Todd Schaeffer, president, Singer Ashland; Tom Lawson, president, Singer EVI; Dana Lawson, vice president, Singer EVI; Jeff Mackey, president, Singer Kittredge; Raymond Fisher, vice president of operations, Singer EVI

Members of Singer Equipment’s leadership team (clockwise from top): Marc Fuchs, sr. vice president, Singer M. Tucker; Todd Schaeffer, president, Singer Ashland; Tom Lawson, president, Singer EVI; Dana Lawson, vice president, Singer EVI; Jeff Mackey, president, Singer Kittredge; Raymond Fisher, vice president of operations, Singer EVI

Companies take on too many projects. Any business can make a list of ten good tasks they want to accomplish in a given year. “Then, you start eight of the ten and you just can’t finish them,” says Singer. A leader should identify the correct two or three to pursue through a disciplined process of understanding how strategic it is, what the likely return will be, what’s the chance of failure and how many resources you have to put against it.

Employees lose touch. Singer read an anthropology study that theorized human beings are happiest when they work in groups of between 10 and 50 people, where people can understand the social connections. So, when possible, he divides his employees into multifunctional teams of of various sizes, each team with its own goal and plan. Singer says, “They’re all tied to each other, they’re tied to the customer and they’re tied to the business.”

Upper management isolates themselves. The more time a CEO spends in their office, waiting for employees to come to them with selected information, the less they are able to lead effectively. “This is not where business happens,” says Singer. “Business happens out there, when the product is delivered to the customer, where the customer uses the product [and] where the customer is talking about what they want to do with their business.”

Companies recruit only within their industry. By investing in training and accelerating the rate at which people can come into a business and be productive, Singer has been able to focus on hiring the most talented people. “This allows us to not feel constrained to only hire people who have industry experience,” he says. “We’re careful when we hire to make sure we have someone that has the type of characteristics of our great employees.”

They focus solely on profits. Yes, a company obviously needs to turn a profit and compensate its employees fairly, but that’s only part of the equation. In order to really motivate employees, you’ve got to build a culture that shows you value them as human beings. “If you create an environment that fits their values — one that allows people to be productive and whole — that’s what makes them excited to bring their best selves to work,” says Singer.