The takeout era has brought along with it some alternative ways of looking at equipment, food halls, campus dining and c-stores.

As restaurants learn to produce everything from multiple-branded menus to family meal kits to bottled retail products out of the same site, that “speaks to the need for flexibility and modularity within the confines of existing kitchens,” notes Dave Henkes, senior principal at foodservice research and consulting firm Technomic. “Equipment is going to be front and center.”

Henkes anticipates multiuse and/or modular equipment growing in prominence: “a combi convection-steamer rather than a traditional oven, or a couple of modular fryers on wheels instead of a bank of fryers.” Additional priorities, he says, will include prep equipment, smaller front-of-the-house refrigeration units, and hot boxes for both holding and delivery.

A takeout-focused future implies “less of an investment in equipment, but different equipment,” suggests Arlene Spiegel, FCSI, who heads up New York-based restaurant and hospitality consulting firm Arlene Spiegel & Associates. “There will be more need for sous vide and rethermalizing equipment, quick-chill systems, Cryovac, things that allow you to make large-batch recipes in advance and retherm quickly,” she says. “There will also be a need for ventless cooking equipment for when you have to set up an additional cookline to meet high-volume demand.”

Operators are researching or purchasing not only equipment for high-volume cooking, chilling, retherming and holding, but also specialized or modular equipment. “Prior to 2020, operators bought equipment that was supercharged to do all kinds of things,” says Aaron J. Barker, FCSI, culinary director at the Concept Kitchen + Bar consultancy firm with offices in Seattle and Chicago. “Now, we’re seeing more emphasis on toasters and waffle makers than on larger equipment. Panini machines are hot again. Everyone’s been yanking out equipment and putting in pizza ovens; in pizza, there are new opportunities across the board.”

Bob Goldin, principal at foodservice consulting firm Pentallect, sees operators’ investments for the post-pandemic future as being modest — “part of the regular replacement cycle, rather than a brand renewal every five years.” Restaurants will prioritize HVAC for good interior air flow, as well as “things that promote sanitation, that are tamper-evident or involve less touch,” Goldin predicts. Operators will also seek out disposable packaging “that offers good temperature retention, is durable and transparent so you can see that the contents are sealed,” he adds.

Market Cafe falls under the FOODWORKS umbrella, which views itself as a small business incubator that sets up mini food halls, largely in corporate spaces.

Market Cafe falls under the FOODWORKS umbrella, which views itself as a small business incubator that sets up mini food halls, largely in corporate spaces.

Food Halls: Problem and Solution

Food halls have been on-trend for some time. The large spaces with a common seating area and a shared back-of-house commissary kitchen appeal to small, local restaurant brands and a smattering of retail food businesses. The format can work well for both commercial spaces and on-site foodservice. But it also became problematic during the pandemic, as central business districts and tourist areas emptied out and pedestrian traffic diminished. According to the Boston Globe, the city’s famed Faneuil Hall Marketplace reached a 25% vacancy rate in 2020.

“Many food halls were doing well because they were conveniently located for daytime traffic, but they are noticing a tremendous lack of customers,” notes Chris Tripoli, FCSI, a hospitality specialist based in Houston. “A lot are pivoting to the ghost kitchen format, bringing in a small crew to make limited menus for third-party delivery, representing all of their food brands. Some have promoted curbside pickup, if they’re conveniently located for that.”

But food halls can also provide opportunities for restaurants to expand and innovate at modest cost. FOODWORKS, a division of Compass Group USA, partners with small restaurants to set up mini food halls in high-traffic locations like office buildings and retail malls, building value for property owners with a group of eateries tailored to the site’s clientele and traffic. The mix can include pop-ups that come and go. With 150 halls in 10 cities and more in the works, Foodworks sees itself as a small-business incubator that “creates community through food.”

Spiegel immediately saw a food hall as the solution when a Native American casino in Oklahoma approached her to rework the 25,000 square feet allotted to its buffet restaurant due to a pandemic-driven need to alter the buffet format.

“A food hall concept will give the operator an opportunity to function even as foodservice changes,” Spiegel explains. “It’s fast service — the equipment is being designed for a three-minute turnaround threshold — but it gives diners a more exciting, high-level culinary experience of mix-and-match food than they’d get with a boring buffet.” The hall will include six concepts from small, local operators, with food from indigenous people showcased. Meals will be either ordered ahead by phone, at a kiosk just outside the hall, or by phone from a dining table within the hall with a runner bringing the meal on a tray with china and silverware.

Operators engineer food hall menus “for quick turnaround and to be limited,” Spiegel notes. “If a concept is not working, it’s really easy to change out because the equipment is generic: heating, holding and chilling, a plug-and-play panini grill, a steam-jacketed kettle, a little pizza oven, a lot of induction. You don’t have to break things up or change the mechanical engineering each time. In fact, food halls are great laboratories for new concepts.”

Texas Tech University set up dedicated pickup counters for meals ordered through its Transact system, which now accounts for most of the food sold through dining plans. Photo by Evan Wilson, photo courtesy of Texas Tech University Hospitality Services

Texas Tech University set up dedicated pickup counters for meals ordered through its Transact system, which now accounts for most of the food sold through dining plans. Photo by Evan Wilson, photo courtesy of Texas Tech University Hospitality Services

At a C&U Near You

While consumers remain skittish about human contact, food courts and food halls provide a reassuring bit of social distancing, says Kip Serfozo, FCSI, Eastern design director for Cini-Little. He’s been working on a project with Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., and its retail foodservice contractor, Aramark.

“When students came back to campus last August, they were freaked out about going to dining halls with a thousand other people, even with social distancing in place,” Serfozo says. “They started swiping their dining-plan cards at the 32 retail outlets because they realized they could go to a smaller, less-populated area to get food without coming into contact with others.”

Serfozo is consulting on the reworking of an old, inefficient food court in the student union into a food hall that will focus on unique, local restaurant brands such as Lafayette’s landmark East End Grill. The 11 menus will include a sushi spot, as well as Italian and Latin fare. The new food hall will offer not only takeout but also delivery to dorms and major campus buildings via Purdue’s fleet of food delivery robots.

Another university that’s rolling out robots, while also rethinking its foodservice more generally, is Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas, with 22 dining locations including branded minimarkets. After noting that a mobile food ordering and pickup system at a single campus food court had created a big uptick in sales volume, Hospitality Services decided to add mobile ordering and pickup at retail and residential dining sites throughout campus, explains Alan Cushman, the department’s manager of business development. Students order and pay through the Transact app, which is designed to sync with the structure of campus dining plans.

The mobile-ordering rollout led to other changes. Before the pandemic, food pickup happened right at the serving line. But “when COVID happened, we encouraged students to prepurchase food for pickup, because that offered greater safety and fewer touch points,” Cushman says. Reallocating some coolers and hot holding cases to the dedicated pickup areas freed up floor space elsewhere and helped staff coordinate traffic flow and social distancing in dining locations. Currently, most of the food served at TTU is ordered online and picked up as packaged meals. To simplify order fulfillment, the department pared down menus and eliminated customization options.

After ending a campus delivery agreement with Grubhub, TTU will phase in the delivery robots this spring. Hospitality Services is also working on other convenience-enhancing technologies like secure food lockers at automated pickup areas to eliminate human-to-human contact in the order handoff. And TTU is modifying plans for a new Union Plaza food court with a retail element to accommodate post-COVID-19 social distancing norms. “The pandemic changed the way we look at things,” Cushman says. “With the new technology and infrastructure we’re putting into play, we have to take a different view of customer service.”

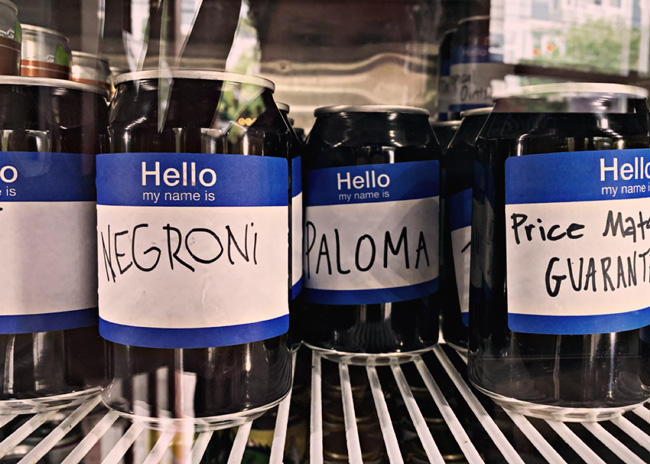

TangleTown Public House in Seattle invested in canning equipment in order to provide house-canned signature cocktails available with takeout meals. The concept is also enhancing its environmentally friendly reputation with deliveries made on electric bikes. Photos courtesy of Aaron J. Barker of Concept Kitchen + Bar

TangleTown Public House in Seattle invested in canning equipment in order to provide house-canned signature cocktails available with takeout meals. The concept is also enhancing its environmentally friendly reputation with deliveries made on electric bikes. Photos courtesy of Aaron J. Barker of Concept Kitchen + Bar

C-stores Stand Strong in the Restaurant Space

College and corporate dining services departments may observe and copy trends in commercial restaurants from time to time, but retail food sectors are mounting an invasion of this noncommercial territory.

“Any grocery store you walk into today has a robust offering of chef-inspired meals that can be ordered quickly and taken home,” says David Bement, senior vice president – sales at TundraFMP Restaurant Supply in Boulder, Colo. “But now we’re seeing the convenience store industry in attack mode, growing at a fast rate, investing in creating a restaurant-like experience for takeout.” He cited his work equipping a c-store that developed its own branded in-store Italian chain offering “high-quality ingredients, pricing aggressively, creating family meals for grab and go.”

Likewise, Spiegel recently completed a consulting project for Swiss Farms, a 13-unit drive-thru c-store chain in Pennsylvania. She sees suburban c-stores less as a threat to restaurants and more of an opportunity. “C-stores have always known that a quarter of their revenue comes from sandwiches and deli items, but now they’re finding that guests want to stay in their cars, come to a pickup area and get a well-known branded meal,” she says. “In areas where people depend on cars, a drive-thru c-store can become a pickup area for nearby restaurants or ghost kitchens. The store could work with three local restaurants, offer four items from each.” C-stores prefer this model she says because it means they no longer need kitchen equipment or staffing; refrigeration, hot holding and labeling equipment are all that’s required.

Spiegel’s advice to restaurants: “It’s no longer all happening under one roof; you need to think about being wherever you can have a point of distribution.” In addition to c-stores, coffee shops that are expanding food offerings may be good partnership opportunities, she suggests.

Her assessment of the restaurant industry future in these fast-changing times? “There’s so much going on! It’s exciting.”

The Unanswered Question:

Who’s in Charge of Food Safety on the Way to the Customer?

With the meteoric rise of third-party delivery, some industry watchers fear that too little attention has been paid to something important: food safety through a supply chain in which the handoff of responsibility gets fuzzy once the food is on its way to the customer.

“I’ve always been concerned about third-party delivery,” says John Reed, FCSI, chef/consultant with Customized Culinary Solutions and Skokie Provisions in Skokie, Ill. “One of the big challenges is your loss of control, particularly if the food is going out to the customer hot.”

David Bement senior vice president – sales at TundraFMP Restaurant Supply in Boulder, Colo., is equally worried. “The way food travels from the kitchen to the customer today is set up for failure,” he declares.

Bement says his customers have not yet made significant capital investments in heated storage and delivery equipment. “They talk about it, they understand they need it, but they don’t know where exactly to invest,” he says. Bement recommends locked heated cabinets for food transit that have recently been released by some manufacturers because they not only hold at proper temperature, but also prevent tampering by the delivery driver.