How is the industry faring in 2021? And, what’s in store for 2022?

When the pandemic first hit the U.S. and wreaked havoc on the restaurant industry, projections about how long the downturn would last and the shape of the recovery were like noses — everyone had one. The industry’s road to recovery remains a long and winding one, marked with plenty of potholes that seem to be keeping restaurants from sustaining any true momentum.

So how is the industry faring in 2021? And, what’s in store for 2022?

Well, it’s complicated.

Restaurant Industry Operating Environment

Consumers will spend $771 billion in restaurants in 2022, per forecast data from Chicago-based market research firm Datassential. This represents an increase from the $608 billion consumers spent in 2020 and the $701.4 billion they will spend this year, per Datassential’s projections. By 2023, consumers’ expenditures on prepared food and nonalcoholic beverages will total $817 billion.

Consumers will spend $771 billion in restaurants in 2022, per forecast data from Chicago-based market research firm Datassential. This represents an increase from the $608 billion consumers spent in 2020 and the $701.4 billion they will spend this year, per Datassential’s projections. By 2023, consumers’ expenditures on prepared food and nonalcoholic beverages will total $817 billion.

In terms of growth rates, industry sales declined 29.6% overall in 2020, per Datassential. This year, the industry will grow at a rate of 10.4% compared to last year’s total revenues, and next year it will experience a 4.9% growth rate. In 2023, when the industry finally exceeds 2019 revenues, its overall growth rate will be 1%, per Datassential.

“The road ahead remains long. So, 2022 will continue to be a year of transition for the industry. Industry sales will continue to move forward, but the potholes will still be there in 2022. Consumers will continue to be very deliberate in terms of how they spend their food dollar,” says Hudson Riehle, senior vice president of research for the National Restaurant Association. “Even though there are challenges in place, the industry will continue to increase the proportion of the food dollar spent away from home.”

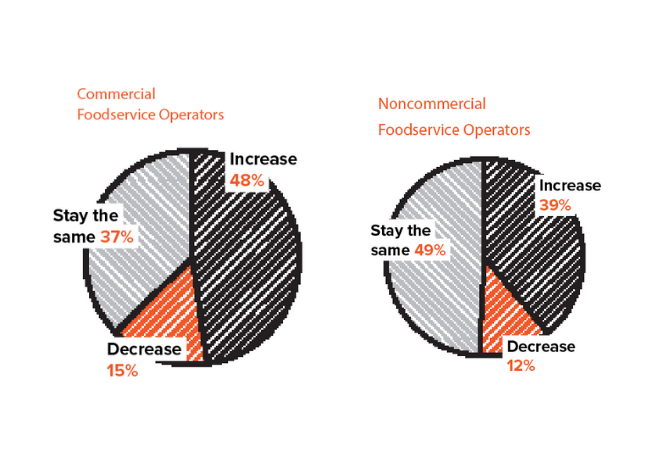

Source: FES Forecast 2022Despite all the challenges from the pandemic, the main reasons consumers want to patronize restaurants remain the same: convenience and socialization. “Convenience is evident in the use of off-premises options. And socialization is evident in the pent-up demand for on-site,” Riehle says. “For the table-service segment, the socialization component will be the most important. When consumers return to restaurants, they are reminded why that on-site dining experience was so important to them. It’s important for table-service operators to engage consumers and bring them back to a hospitable environment with such good food quality.”

Source: FES Forecast 2022Despite all the challenges from the pandemic, the main reasons consumers want to patronize restaurants remain the same: convenience and socialization. “Convenience is evident in the use of off-premises options. And socialization is evident in the pent-up demand for on-site,” Riehle says. “For the table-service segment, the socialization component will be the most important. When consumers return to restaurants, they are reminded why that on-site dining experience was so important to them. It’s important for table-service operators to engage consumers and bring them back to a hospitable environment with such good food quality.”

Labor, or more precisely the lack of it, will impact the industry’s ability to hasten its recovery. In its 2021 State of the Industry Mid-Year Update, the National Restaurant Association reports that 75% of operators say recruiting and retaining employees are their top challenges.

“One of the things the pandemic did was give people who work in the hospitality field a chance to take a step back and ask is it worth it for me to stay in this industry,” says Warren Solochek, principal of Insights to Opportunities in Chicago. “There have been a number of people — servers, back-of-house workers, etc. — who have said I don’t want to do this anymore. Scarcity of labor will continue to have a negative effect on the industry. This is particularly true of full-service restaurants, who will have to cut back on hours because they can’t find enough people to work.”

And that can lead to longer service times, be it waiting for a table or for staff to complete an order or both. “This will force people to keep turning to the drive-thru, carryout and delivery because the on-premises service levels are diminished,” Solochek notes. “In some instances, the time between placing your order and getting your beverages, which should be very quick, has gotten to be pretty long. And the times between courses being served are longer. It’s not fun for anyone involved. Operators often find themselves rushing orders out of the kitchen with inexperienced people. It’s going to be really difficult for the industry to hire enough people to get back to smoother running operations the way they were prior to the pandemic. Even with higher industry wages, people can go to other places and make more.”

This is where technology can help. “The factor going ahead is the use of technology to increase the productivity of a typical restaurant’s operations. That means labor is reallocated,” Riehle says. “Some of that is moved down to the supply chain too.”

This is where technology can help. “The factor going ahead is the use of technology to increase the productivity of a typical restaurant’s operations. That means labor is reallocated,” Riehle says. “Some of that is moved down to the supply chain too.”

One example of technology playing a greater role in helping offset labor woes is Dunkin’s first digital-only location, which the chain debuted in September. Customers at the Boston restaurant place their orders using the Dunkin’ app or via an in-store kiosk. Guests fetch their orders from what the chain describes as an enhanced pickup area. Interestingly enough, while guests place orders digitally, the chain claims it will still employ the same number of people as it would at a traditional location. This is an example of technology not reducing labor but potentially making more effective and efficient use of what a restaurant already has.

Source: FES Forecast 2022As a result of the changes, challenges and opportunities described here, the restaurant industry almost has two different recoveries taking place: one for quick-serve restaurants and one for the other segments. “You can see that when you review the market research. The quick-service operators have recovered faster than some other segments because they can drive more volume out of their locations,” Solochek says. “Time has value, and people are saying, ‘I will go get it myself’ and that plays into the strengths of QSRs.”

Source: FES Forecast 2022As a result of the changes, challenges and opportunities described here, the restaurant industry almost has two different recoveries taking place: one for quick-serve restaurants and one for the other segments. “You can see that when you review the market research. The quick-service operators have recovered faster than some other segments because they can drive more volume out of their locations,” Solochek says. “Time has value, and people are saying, ‘I will go get it myself’ and that plays into the strengths of QSRs.”

By the end of 2022, sales at quick-service restaurants will be at 107% of the segment’s 2019 revenues, per Datassential. In contrast, the more table-service-centric segments will continue to show improvement but will remain less than their 2019 levels, like midscale dining (81%), casual dining (91%) and fine-dining (87%). Even the fast-casual segment, which served as the industry’s growth vehicle for a long time, won’t exceed its 2019 revenue levels until 2023, per Datassential.

Quick-service operators continue to take notice of consumers’ evolving dining habits and adjust their plans accordingly. “Their new prototypes have smaller footprints, smaller dining areas and, when they can, multiple drive-thru lanes,” Solochek says. “They are reacting to people’s preference of wanting their orders as fast as they can get it. All those new designs are all focused on throughput. These new designs enable operators to make their footprints smaller, which saves on building costs, and it may make their real estate costs lower in the long run. These operators are rewarding people who order ahead. That reward includes faster drive times. A bunch of things need to happen back of house, but you can manage that.”

One notable example of this approach made headlines back in August when Taco Bell unveiled its Defy prototype. The 3,000-square-foot restaurant, set to open in the summer of 2022 in Minnesota, will take a vertical approach to enhancing speed of service by placing the kitchen on the second floor of the restaurant. The unit will feature four drive-thru lanes, including three that will serve only mobile or delivery order pickups. The fourth lane will handle traditional drive-thru traffic. Digital check-in screens will allow mobile order customers to scan in their order via a unique QR code and then pull forward to pick up their meals. Staff will deliver food via a proprietary lift system. The unit will also feature two-way audio and video technology that lets customers interact directly with the team members above in real time.

No story about restaurant operating conditions would be complete without a nod to the industry’s ongoing supply chain challenges. Roughly 4 out of 5 table-service operators report supply chain shortages and that jumps to 7 out of 10 when homing in on the quick-service segment, Riehle says. “The supply chain challenges have added fuel to the fire to simplify the menu,” he says. “When you think about how consumers order both remotely and on-site, it becomes apparent that menu simplification will continue. Menu reengineering is driven by not only price point considerations but what is available on a long-term basis too. The period from 2009 to the pandemic was the longest period of post-war economic expansion. And it allowed menus to become more complicated and expansive because the underlying economy could support that. Now the challenges with the economy and the supply chain have realigned operators’ approach.”

The supply chain challenges are not limited to the ingredients foodservice operators use in executing their menus. They also pertain to production of foodservice equipment and supplies. Manufacturers report ongoing supply chain challenges related to the sourcing of metals, component parts and, once they make the products, shipping, per the North American Association of Food Equipment Manufacturers. In fact, 45% of NAFEM member companies say challenges in sourcing metals alone have led to two- to three-month delays in shipping finished goods to operators.

2022 and Beyond: A Foodservice Odyssey

When will things get back to normal? “At this point, one out of five operators thinks it never returns to normal and 44% think it’s more than a year,” Riehle says.

One thing’s for certain — the industry will be different moving forward due to increased technology use, changes in menu development and ongoing labor issues. “The industry is like a large tree that gets toppled by a windstorm. That tree continues to grow but, the branches of growth are different from pre-pandemic,” Riehle says. “It will be different but in a positive way. There are new avenues in channels of growth that add diversity to the industry. The industry now has many additional avenues of growth.”

For example, ghost kitchens and virtual brands increase consumers’ points of access to restaurants, Riehle notes. And during the pandemic, consumers became more comfortable with digital ordering — they had to as it was often the only game in town. Even the shift to off-premises got a boost during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, 61% of all restaurant orders were consumed off-premises, Riehle notes. “During the depths of the pandemic, that jumped to 90% because the restrictions were so severe. That’s about 80% now. It’s not likely, though, this will drop back down to the 60% range. There will be some gradual shifting as the months go by, but that off-premises market will remain more important for the consumer and the operator.”

The industry will also continue to grapple with labor challenges in the coming months. “That’s due to the nation’s core demographics. The nation will continue to age,” Riehle says. “And during normal times, one of the industry’s top challenges was recruitment. The demographic impact on America’s workforce is not limited to the restaurant industry. One thing the pandemic did was led some baby boomers into retirement.”

One significant issue that will affect the future of the restaurant industry is when and how business districts and city centers bounce back from the pandemic. “Prior to the pandemic, these areas had high growth and restaurant sales surged. Then comes the pandemic and people leave and sales tumble,” Riehle says.

Many companies continue to kick around the idea of a hybrid work environment. “You are never going to see the office environment the way it was pre-pandemic. There will be larger groups of people working from home full-time or at least a few days a week,” Solochek predicts. “Offices won’t be the central hub of the work environment.”

If that scenario plays out, “the loss of business could be as high as 20% due to the loss of having those people in these city centers week after week, month after month,” Riehle predicts.

The uncertainty surrounding back-to-work plans impacts more than the restaurants that operate in the central business districts. It also impacts the corporate feeders, and as of August, Datassential reported 19% of B&I operators were completely closed. Looking ahead to 2022, Datassential projects B&I revenues will only achieve 76% of 2019 levels. In other words, there’s still a ways to go in this segment’s recovery.

The uncertainty surrounding back-to-work plans impacts more than the restaurants that operate in the central business districts. It also impacts the corporate feeders, and as of August, Datassential reported 19% of B&I operators were completely closed. Looking ahead to 2022, Datassential projects B&I revenues will only achieve 76% of 2019 levels. In other words, there’s still a ways to go in this segment’s recovery.

As the adage goes, when one door closes another opens. “You will see an acceleration of operators in central business districts closing because the demand will not be as great. On the other hand, you will see greater demand for restaurants in suburban areas because the people who work from home will want that convenience,” Solochek predicts. “But those restaurants better cater to automobiles and up their game in terms of carryout and delivery. But the big question remains: Can they find enough labor?”

What does this all mean for the coming year? Well, once again, it’s complicated, as Datassential’s projections for noncommercial segments indicate. For example, in healthcare, senior living will hit 100% of its 2019 revenue levels in 2022 followed closely by long-term care at 98%, per Datassential. Hospitals, in contrast, will only be at 88% of 2019 revenues by the end of next year. This is due to a variety of reasons, including the fact that a large portion of hospital foodservice revenue comes from people working at or visiting these healthcare campuses. As these employers continue to flesh out their return-to-work approach and policies about having guests on campus, expect these revenues to continue to evolve.

In other words, the industry will remain a work in progress for the next year or so. “In 2022, the industry as a whole will show some growth relative to 2021, if for no reason other than the first quarter of 2021 was so weak because of COVID. So, the year-over-year comparison will be favorable,” Solochek says. “The deeper you get into 2022, the year-over-year comps will still show growth but just not as much. The demand is still there as consumers love going to restaurants. The question becomes, “Where can I spend it? Where I can have a satisfactory experience?”